Introduction: Transnational Solidarity

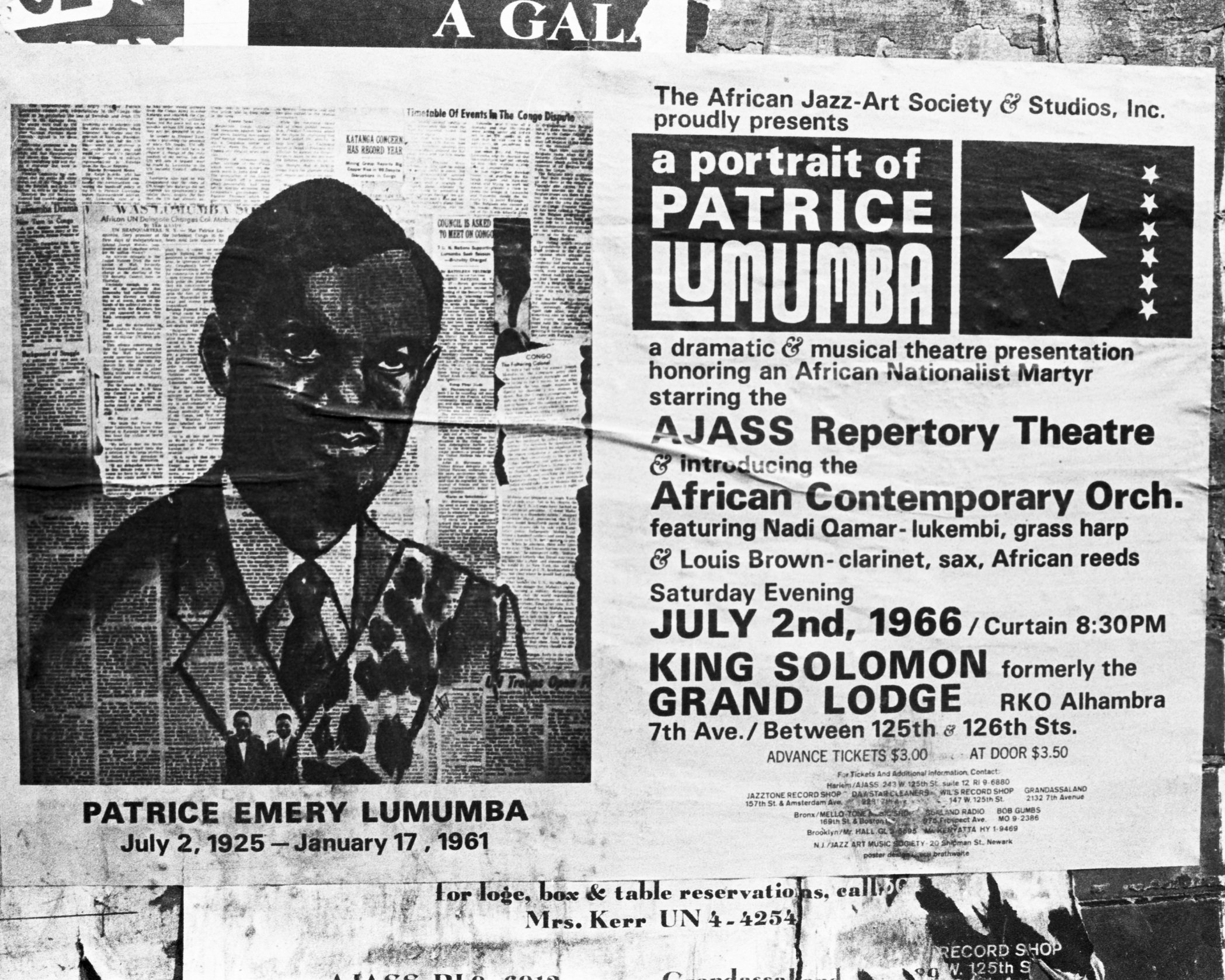

Advertisement for the musical theatre production “A Portrait of Patrice Lumumba” on the brick wall of a building in Harlem, 1966. © Alabama Department of Archives and History, Jim Peppler The Southern Courier Photograph Collection

The Civil Rights Movement in the United States was connected to the international struggle against colonialism. Such well-known African American historians as W. E. B. Du Bois and Carter G. Woodson had long linked U.S. racism and segregation to the colonial system in Africa and other parts of the world. Nico Slate’s landmark book, Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom in the United States and India, and Sterling Johnson’s Black Globalism: The International Politics of a Non-State Nation highlight the 19th century origins of Black international thought and the shared struggle against colonialism that connected Du Bois, Gandhi, and other Indian and African American activities. These figures built upon the work of Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association, an organization that, according to Adam Ewing in The Age of Garvey: How a Jamaican Activist Created a Mass Movement and Changed Global Black Politics, shaped a global Black politics in the early 20th century and laid the groundwork for later efforts.

By the 1940s, African American activists forged direct connections with their counterparts in Africa and Asia. As Penny Von Eschen shows in Race Against Empire, African American activists turned to their counterparts in the decolonizing world as inspiration for their struggle in the United States. These connections were maintained throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

In the late 1960s, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panther Party (BPP) linked their struggles with decolonization and political struggles in Africa, Asia, and South America, although consciousness of these struggles were evident as early as the 1960 founding conference of SNCC. These organizations placed the struggle in South Africa into a larger effort to fight against U.S. and Western imperialism.

At the same time that SNCC and the BPP sought to develop an international coalition of oppressed peoples, college students around the world also organized demonstrations to advocate for expanded democracy and political rights. The Mexico Student Movement, for instance, challenged the one party system in Mexico and led a large-scale demonstration in 1968. Students also led efforts in Italy, Czech Republic, France, Argentina, and China. Quinn Slobodian’s Foreign Front: Third World Politics in Sixties West Germany brings to light how German student activists learned from their counterparts in the Congo and other parts of Africa. And, as Martin Klimke shows in The Other Alliance: Student Protest in West Germany and the United States in the Global Sixties, these German activists built a non-state transnational “alliance” that challenged Cold War politics and government oppression.

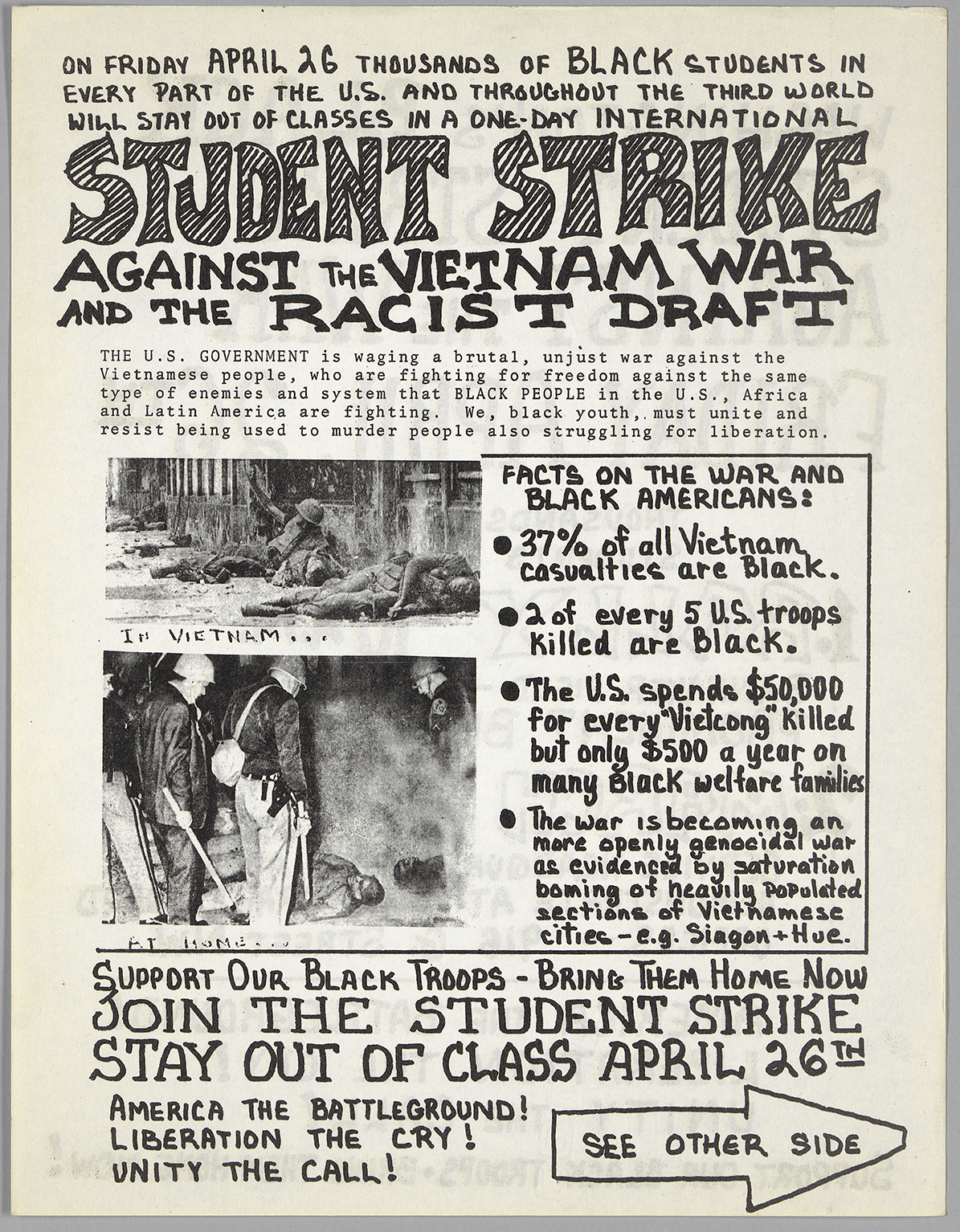

Flier advertising a student strike against the Vietnam War on April 26, 1968. Source: Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

The mass mobilization of college students across the world reflected the growing political awareness of young people in the 1960s and their efforts to end the war in Vietnam and the vestiges of colonialism and dictatorship. Judy Tzu-Chun Wu’s book, Radicals on the Road: Internationalism, Orientalism, and Feminism, demonstrates the broad international coalition forged by young activists in the late 1960s and early 1970s that transcended narrow national, gender, and racial identities.

As SNCC veteran Timothy L. Jenkins remarked,

History may have forgotten, but we must not, that before Dr. King gave his now much-remembered Riverside Church declaration, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had already uniquely and notoriously condemned the international hypocrisy of the United States in Vietnam, Africa, and the Caribbean in the face of the parallel Black liberation movement throughout the southern United States.

We knew all too well the dreadful parallel of domestic martyrs like Samuel Younge as unsung victims of federal indifference while the government did not delay in condemning those who refused to fight a racial and fraudulent war abroad.

The lessons and readings in this section encourage students to consider movements for social justice through a global lens and to draw relevant international connections today. ■