South African Unions Struggle for Justice

Lesson by Bill Bigelow

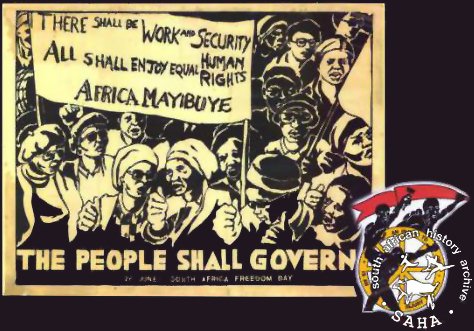

Screen Training Project for the United Democratic Front, 1986, South African History Archive

The South African anti-apartheid movement is often mischaracterized in the United States as simply a fight for political rights, culminating in the election of Nelson Mandela as the country’s first freely chosen president. However, a crucial component of the broader anti-apartheid struggle was the Black union movement. Black unions linked their political objectives for an end to racial oppression to their campaigns for higher wages and better working conditions, and aimed to democratize power relations in the workplace. This lesson invites students to imagine themselves as Black union activists at the height of the anti-apartheid movement in the 1980s and poses them problems that confronted real-life organizers at the time.

Note that throughout the description of the activity, a number of racial designations are used. About 10 percent of South Africans, people the government decided were of mixed race, were classified “Colored.” Almost 75 percent of South Africans were classified as “African.” The government then divided them further into tribal groups such as Xhosa, Zulu, and Venda — an effort seen as divide-and-conquer by the anti-apartheid movement. Even though South Africans of European ancestry spoke two languages, Afrikaans and English, and had important cultural differences, the government counted them as one unified group: white.

For background activities on South African apartheid, see Strangers in Their Own Country: A Curriculum Guide on South Africa, by Bill Bigelow (Africa World Press, 1985), from which this activity is adapted. For additional resources see Africa Access, which provides online, scholarly reviews of over 900 resources for teaching about Africa and Africa World Press, which is dedicated to the publication and distribution of books on the African World.

Grade Level: Grades 7+

Time Required: Two to three class periods.

Congress of South African Trade Unions, 2005, South African History Archive

Goals and Objectives

Students will become familiar with the Freedom Charter, the most influential document in the movement for equality in South Africa.

Students will encounter some of the difficulties of Black unions in working for workers’ rights during the apartheid era in South Africa.

Students will explore the relationship between working for immediate union objectives and long-term political objectives.

Students will practice democratic decision-making.

Materials Needed

Handout 1: The Freedom Charter

Handout 2: Black Union Activist

Handout 3: Planning the Strike: Questions

Procedure

Have students read Handout 1: The Freedom Charter. (Depending on your preference, this may be assigned for homework or read aloud in class. Whichever you choose, make sure students are familiar with the document before proceeding with the lesson.)

Discuss the Freedom Charter (download the full lesson for suggested questions).

Ask students to imagine themselves as Black workers in South Africa who support the Freedom Charter and want it to become a reality. They will each be receiving a role sheet (Student Handout 2) describing the conditions at the factory in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, where they work. (Point out Port Elizabeth on a map and show its proximity to the Transkei and Ciskei, two of the Black “homelands” created by the white South African government.)

Distribute a copy of Handout 2: Black Union Activist to students. Read the handout aloud or have them read it to themselves. “Interview” a number of students after they have read the handout to insure that the class is clear on the role everyone will be assuming.

Explain to students that now that the strike is on they will be facing a number of difficult decisions. Because theirs is a democratic union and because they believe in equality, no one will be around to tell them what to do. If the strike is to succeed it will only be because they were able to make it succeed — together. Therefore, you, the teacher, will play no role in their discussions. Once their strike meeting begins you will only be an observer. It will be up to the entire class to decide how to make decisions and what decisions to make. Explain that they will be given a handout to help them figure out the important questions to answer, but the answers will be theirs.

Once they understand that you won’t assist with their deliberations, you might want to discuss some of the ways they could go about making decisions. For example, they could select a chairperson who would then call on individuals to speak, and propose when votes might be taken. Perhaps they want to avoid leaders entirely — students might raise hands with the last person to speak calling on the next speaker and so on. Or a rotating chairperson might be chosen — one chair per question, for example. The teacher’s job is merely to help students make their own decisions. This is an essential part of the roleplay.

When you feel they have a good understanding of their role and you’ve discussed some of the decision-making methods they might use, distribute Handout 3: Planning The Strike: Questions. Emphasize one last time before they begin that their goal is twofold: 1) to win the strike, and 2) to contribute toward ending apartheid and building a nonracial democracy. Also remind them that they should answer each question as fully as possible. Tell them you will be available only if they have difficulty understanding one of the seven questions on the handout.

Allow them to begin their meeting. Because students generally are not used to organizing a discussion without the assistance of an authority figure, they may experience some rough going. That’s fine. Let them discover their own problems and solutions. Intervene only if you sense that students are hopelessly frustrated, and then only to help them get a clear decision-making process set up. As the meeting progresses, take notes on both their decision-making successes and failures as well as on the different ideas and arguments raised in answering the questions.

At the conclusion of the strike meeting you might have students write an evaluation of the decisions they made and the process that brought them to those decisions. Taking this break for reflection sometimes enables students to discuss their experience a little more thoughtfully.

Any discussion of this roleplay will depend upon the specific decisions students reached in their talks. The download of this lesson includes guidelines for student discussion.

Questions about the students’ process of decision-making could follow discussion of their actual decisions, such as:

Is it a common part of your education to be taught decision-making skills — how to work and think as a group without an authority figure leading you? If not, why isn’t this skill taught more?

Would any groups in our society feel threatened by high schools graduating students who were both comfortable making decisions collectively and who expected to continue to operate that way in their work lives?

© 1985 Africa World Press. Reprinted with permission from Bill Bigelow, Strangers in Their Own Country (Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press, 1985).