What We Want

Primary Document by Kwame Touré (Stokely Carmichael)

Stokely Carmichael, first with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and then with the Black Panthers, was among the first to articulate the difference between the Black Power and Civil Rights Movements. His use of the term “Black Power” after James Meredith’s March Against Fear in 1966 popularized the idea. The emergence of the Black Power movement marked a shift in the public perception of the U.S. Black liberation struggle.

Separatism, the determination of a particular group of people to resist assimilating to the majority culture, has a long history in the United States. Nearly every wave of immigrants to this country has at least initially tried to maintain the integrity of its native culture. Some, like the Amish, have succeeded. Early in this century, Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey urged American Black people to reject the dream of integration and to return to Africa. Garvey’s philosophy of Pan-Africanism re-emerged in the 1960s in the cry for “Black Power.” The following excerpt from Kwame Touré’s “What We Want” offers a rationale for the notion of an independent Black community.

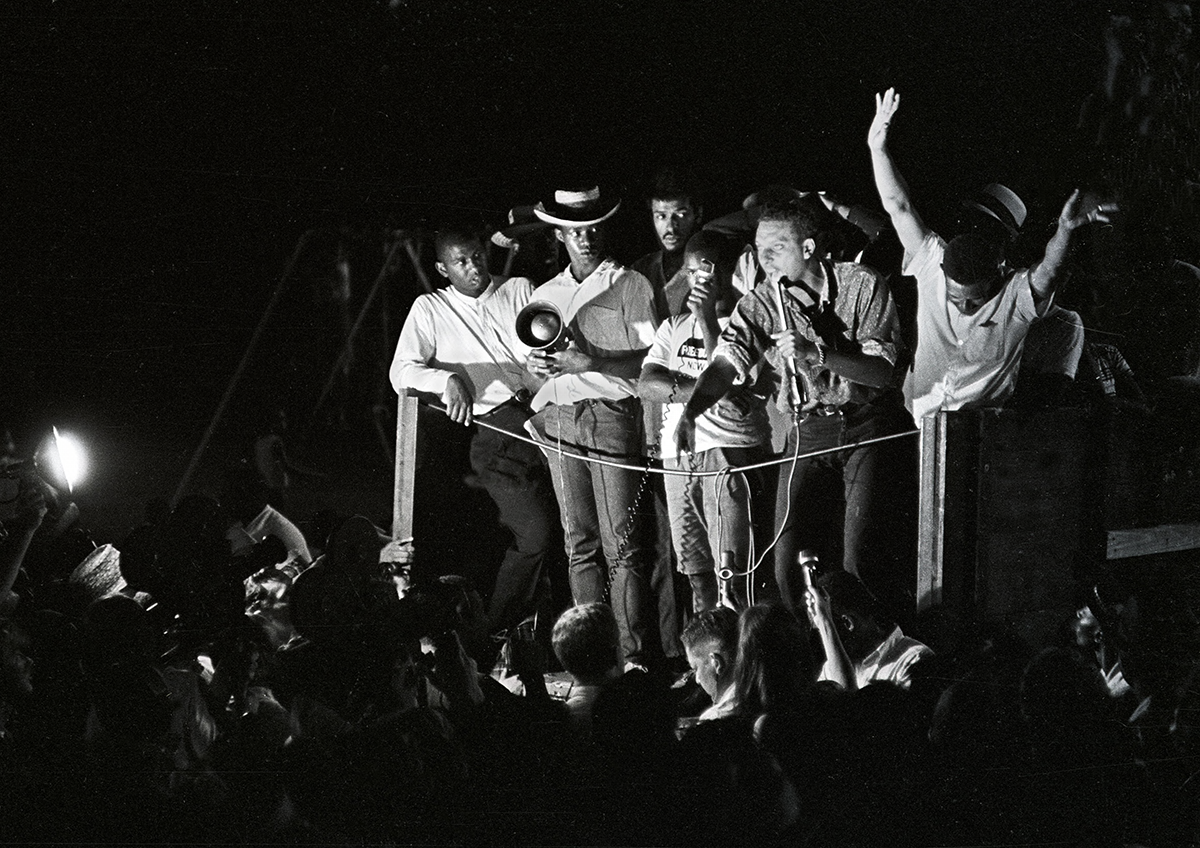

Stokely Carmichael delivers his “Black Power” speech at a rally in Broad Street Park in Greenwood, Mississippi, during the Meredith March Against Fear, June 1966. Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

Ultimately, the economic foundations of this country must be shaken if Black people are to control their lives. The colonies of the United States — and this includes the Black ghettoes within its borders, north and south — must be liberated. For a century, this nation has been like an octopus of exploitation, its tentacles stretching from Mississippi and Harlem to South America, the Middle East, southern Africa, and Vietnam; the form of exploitation varies from area to area but the essential result has been the same — a powerful few have been maintained and enriched at the expense of the poor and voiceless colored masses.

This pattern must be broken. As its grip loosens here and there around the world, the hopes of Black Americans become more realistic. For racism to die, a totally different America must be born.

This is what white society does not wish to face; this is why that society prefers to talk about integration. But integration speaks not at all to the problem of poverty, only to the problem of Blackness. Integration today means the man who “makes it,” leaving his Black brothers behind in the ghetto as fast as his new sports car will take him. It has no relevance to the Harlem wino or to the cottonpicker making three dollars a day. As a lady I know in Alabama once said, “the food that [African American Nobel Peace Prize winner] Ralph Bunche eats doesn’t fill my stomach.”

Integration, moreover, speaks to the problem of Blackness in a despicable way. As a goal, it has been based on complete acceptance of the fact that in order to have a decent house or education, Blacks must move into a white neighborhood or send their children to a white school. This reinforces, among both Black and white, the idea that “white” is automatically better and “Black” is by definition inferior. This is why integration is a subterfuge for the maintenance of white supremacy. It allows the nation to focus on a handful of Southern children who get into white schools, at great price, and to ignore the 94 percent who are left behind in unimproved all-Black schools. Such situations will not change until Black people have power — to control their own school boards, in this case. Then Negroes become equal in a way that means something, and integration ceases to be a one-way street. Then integration doesn’t mean draining skills and energies from the ghetto into white neighborhoods; then it can mean white people moving from Beverly Hills into Watts, white people joining the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. Then integration becomes relevant.

White America will not face the problem of color, the reality of it. The well-intended say: “We’re all human, everybody is really decent, we must forget color.” But color cannot be “forgotten” until its weight is recognized and dealt with. White America will not acknowledge that the ways in which the country sees itself are contradicted by being Black — and always have been. Whereas most of the people who settled this country came here for freedom or for economic opportunity, Blacks were brought here to be slaves. When the Lowndes County Freedom Organization chose the black panther as its symbol, it was christened by the press as “the Black Panther Party” — but the Alabama Democratic Party, whose symbol is a rooster, has never been called the White Cock Party. No one ever talked about “white power” because power in this country is white. All this adds up to more than merely identifying a group phenomenon by some catchy name or adjective. The furor over that black panther reveals the problems that white America has with color and sex; the furor over “Black power” reveals how deep racism runs and the great fear which is attached to it.

Whites will not see that I, for example, as a person oppressed because of my blackness, have common cause with other Blacks who are oppressed because of blackness. This is not to say that there are no white people who see things as I do, but that it is Black people I must speak to first. It must be the oppressed to whom SNCC addresses itself primarily, not to friends from the oppressing group.

From birth, Black people are told a set of lies about themselves. We are told that we are lazy — yet I drive through the Delta area of Mississippi and watch Black people picking cotton in the hot sun for 14 hours.

We are told, “If you work hard, you’ll succeed” — but if that were true, Black people would own this country. We are oppressed because we are Black — not because we are ignorant, not because we are lazy, not because we are stupid (and got good rhythm), but because we’re Black.

I remember that when I was a boy, I used to go to see Tarzan movies on Saturday. White Tarzan used to beat up the Black natives. I would sit there yelling, “Kill the beasts, kill the savages, kill ‘em!” I was saying: Kill me. It was as if a Jewish boy watched Nazis taking Jews off to concentration camps and cheered them on. Today, I want the chief to beat the hell out of Tarzan and send him back to Europe. But it takes time to become free of the lies and their shaming effect on Black minds. It takes time to reject the most important lie: that Black people inherently can’t do the same things white people can do, unless white people help them.

The need for psychological equality is the reason why SNCC today believes the Blacks must organize in the Black community. Only Black people can convey the revolutionary idea that Black people are able to do things themselves. Only they can help create in the community an aroused and continuing Black consciousness that will provide the basis for political strength. In the past, white allies have furthered white supremacy without the whites involved realizing it — or wanting it, I think. Black people must do things for themselves; they must get poverty money they will control and spend themselves, they must conduct tutorial programs themselves so that Black children can identify with Black people. This is one reason Africa has such importance: The reality of Black men ruling their own nations gives Blacks elsewhere a sense of possibility, of power, which they do not now have.

This does not mean we don’t welcome help, or friends. But we want the right to decide whether anyone is, in fact, our friend. In the past, Black Americans have been almost the only people whom everybody and his momma could jump up and call their friends. We have been tokens, symbols, objects — as I was in high school to many young whites, who liked having “a Negro friend.” We want to decide who is our friend, and we will not accept someone who comes to us and says, “If you do X, Y, and Z, then I’ll help you.” We will not be told whom we should choose as allies. We will not be isolated from any group or nation except by our own choice. We cannot have the oppressors telling the oppressed how to rid themselves of the oppressor.

I have said that most liberal whites react to “Black power” with the question, What about me?, rather than saying: Tell me what you want me to do and I’ll see if I can do it. There are answers to the right question. One of the most disturbing things about almost all white supporters of the movement has been that they are afraid to go into their own communities — this is where the racism exists—and work to get rid of it. They want to run from Berkeley to tell us what to do in Mississippi; let them look instead at Berkeley. They admonish Blacks to be nonviolent; let them preach nonviolence in the white community. They come to teach me Negro history; let them go to the suburbs and open up freedom schools for whites. Let them work to stop American racist foreign policy; let them press this government to cease supporting the economy of South Africa.

There is a vital job to be done among poor whites. We hope to see eventually a coalition between poor Blacks and poor whites. That is the only coalition that seems acceptable to us, and we see such a coalition as the major internal instrument of change in American society. SNCC has tried several times to organize poor whites; we are trying again now with an initial training program in Tennessee.

. . .

As for white America, perhaps it can stop crying out against “Black supremacy,” “Black nationalism,” “racism in reverse,” and begin facing reality. The reality is that this nation, from top to bottom, is racist; that racism is not primarily a problem of “human relations” but of an exploitation maintained — either actively or through silence — by the society as a whole. Camus and Sartre have asked, can a man condemn himself? Can whites, particularly liberal whites, condemn themselves? Can they stop blaming us, and blame their own system? Are they capable of the shame that might become a revolutionary emotion?

We have found that they usually cannot condemn themselves, and so we have done it. But the rebuilding of this society, if at all possible, is basically the responsibility of whites — not Blacks. We won’t fight to save the present society, in Vietnam or anywhere else. We are just going to work, in the way we see fit, and on goals we define, not for civil rights but for all our human rights.

This document is in the public domain. Reprinted from Rereading America, ed. Gary Colombo, Robert Cullen, and Bonnie Lisle (St. Martin’s Press, 1989).