Desegregation Court Cases Before and After Brown v. Board of Education

Reading from the Brown Foundation on Educational Equity, Excellence, and Research with additions from Teaching for Change

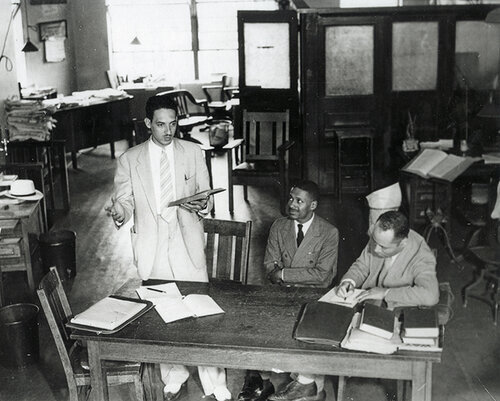

Thurgood Marshall (l), Donald Gaines Murray (c) and Charles Hamilton Houston (r) at Howard University Law School in 1935 as they prepare to challenge Jim Crow at the University of Maryland law school. Courtesy Washington Spark.

For more than a century, African Americans and other racial and ethnic groups have sought to ensure access to equal educational opportunity. Religion, education, and community have proven to be the cornerstones of self-determination on the part of African Americans. One of the most prominent examples of this cornerstone concept can be found in the early and unrelenting legal challenges to segregated public schools.

While most people have heard of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, it was by no means the first attempt to use the courts to secure access to equal education regardless of race, ethnicity, or national origin.

Throughout U.S. history, families have pursued legal action in the hopes of achieving educational equality for their children. Individuals or small groups of parents appear to have acted on their own in the earliest cases. In later cases, state and national strategies of the NAACP clearly were at work. Slowly, the actions of attorneys representing parents and school children chipped away at legal segregation in schools. (Despite the Supreme Court ruling, schools in many cities are more segregated now than they were before Brown v. Board.) Court decisions began to provide some measure of protection for the idea of equality even in the bleakest of times for African Americans.

Earliest Reported Case, 1849: Roberts V. The City of Boston

In the early 1840s, African American parents in Boston began publicly expressing resentment because they were taxed to support schools that their children were not allowed to attend. They began petition drives to close down the segregated schools. They petitioned in 1845, and again in 1846 and 1848, without success. The final effort was undertaken in 1849 under the legal leadership of attorneys Charles Sumner, who went on to become a U.S. senator, and Robert Morris, an African American activist who shared the title of “abolitionist” with his colleagues.

The case became known as Roberts v. The City of Boston. In their petition to the Massachusetts Supreme Court, attorneys for the African American parents outlined the circumstances they believed to be unlawful. Parents explained how their children had been denied enrollment in all Boston schools except the segregated Smith School. The Roberts case was unsuccessful because authorities reasoned that special provisions had been made for “colored” students to have a school.

1881-1949: The Kansas Cases

Before Brown v. Board of Education became part of the national legal landscape, African American parents in Kansas had initiated 11 court challenges to segregated public schools. During a span of nearly 70 years — from 1881 to 1949 — the Kansas Supreme Court became the precedent for the constitutional question of public-school segregation. The free state heritage, central geographical location, and makeup of its population positioned Kansas to play a central role in the major questions of educational freedom and equality. Kansas law at first had little to say on the subject of school segregation.

In 1868 the law allowed, but did not require, separate schools. Some schools admitted children without discrimination, and one of the first superintendents of public instruction, Peter McVicar, vocally opposed segregated schools. The increase in the African American population with the arrival of the “Exodusters” from the South in the 1870s, however, hardened attitudes in Kansas. Some schools began to separate children by race.

In 1877, the Kansas legislature passed a statute specifically allowing first-class cities (those with populations of 15,000 or more) to run separate elementary schools. This law remained in effect into the 1950s. However, with the exception of Wyandotte, high schools were not segregated in Kansas.

African American parents in Kansas challenged equal access to public schools through these legal cases, several of which are described in detail below.

1881: Elijah Tinnon v. The Board of Education of Ottawa (Kansas)

Elijah Tinnon was an African American parent who spoke and acted for equal educational opportunity in Kansas before the concept had a name. Tinnon, listed in the census as a laborer born in Arkansas before the Civil War, addressed the Ottawa, Kan. Board of Education in 1876. He and six other parents questioned the placement of their children in a separate room within the Central School and the qualifications of the teacher assigned to this room. The board’s committee looking into the matter contended that most African American parents were in favor of the Black teacher, whose certification to teach the board belatedly checked into. The protesting parents were not deterred. Superintendent of Schools William Wheeler advised the school board that Tinnon and other parents “demanded admission for their children into the proper grades of the public school.” The board then voted “that the colored class lately taught by Mr. Wade be discontinued, and the pupils in attendance there be assigned to the various rooms in graded school.” The board obtained the teacher’s resignation and paid him one month’s wage of $40. Equal access to education in Ottawa appeared to have been decided.

However, less than four years later Tinnon was again at odds with board policies. The board opened a one-room school for Black children, grades 1 to 6, in a frame building across the street from the brick Central School. Tinnon’s demand that his 7-year-old son Leslie be assigned to the brick school, the school nearest his home, was refused. Tinnon took his case to the courts. He was the first of more than a dozen little-known African American parents to challenge school segregation through to the Kansas Supreme Court. The 1881 Tinnon case was first tried in District Court in Franklin County. Judge Nelson D. Stephens cited the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution, guaranteeing individual rights of citizenship, among his reasons for deciding in favor of Tinnon. The Ottawa School Board appealed the decision to the Kansas Supreme Court. In words anticipating school decisions to come, Judge Daniel M. Valentine asked in upholding Tinnon, “is it not better for the aggregate of human society as well as for individuals that all children should mingle together and learn to know each other?”

This case had elements of the first desegregation case in Boston, and of later court challenges in Kansas:

1) The challenge became known by one name although several parents were often involved;

2) the victory of one year often disappeared the next year;

3) the jobs of Black teachers were at risk;

4) high schools, with one exception, were open to all; and

5) the courts offered the best avenue for equal access to education.

1891: Knox v. The Board of Education of Independence (Kansas)

Jordan Knox of Independence, Kansas, found himself in a situation similar to Elijah Tinnon. Knox’s daughters, 8- and 10-year-old Bertha and Lilly, passed by one elementary school to reach the Fourth Ward School to which they were assigned. In 1890 their father informed the board of education that he wanted his daughters to attend the school nearest their home. He argued that the Second Ward School had room for additional children. Knox sought legal help to compel the board to honor his request.

When this case was decided in 1891, the Kansas Supreme Court cited the Tinnon case and found no authority for the second-class city of Independence “to exclude from the schools established for white children, the colored children.” Knox and four other parents who joined as plaintiffs won their case and were awarded court costs.

1906: Cartwright v. The Board of Education of Coffeyville (Kansas)

In Coffeyville the school board maintained racially separate grades within Lincoln School. African American students were assigned to one classroom. Eva Cartwright, an African American 6th grader, accompanied by her mother tried to enroll in an all-white 6th-grade class taught by a white teacher. Eva was turned away and sent to the classroom reserved for African American students. Bud Cartwright demanded that his daughter Eva be admitted to the regular classroom for her grade level.

One of his attorneys was James A. Guy, an African American lawyer who moved to Kansas from Ohio. In 1906, the Kansas Supreme Court ruled for Cartwright based on Kansas law governing schools in second-class cities. The legal issue in second-class cities seemed to be settled. The court’s decision stated that the board of education had no power to exclude African American students from schools established for white children in the absence of a law that authorized such power in second-class cities.

1903: Reynolds v. The Board of Education of Topeka

Decisions affecting other larger cities were mixed. William Reynolds lost his 1903 case against the Board of Education of Topeka. All children had attended the same building in the Lowman Hill District until it burned down in 1900. The board purchased a new site and erected a two-story brick building. Black pupils were assigned to the older Douglas building, which was moved to the area. Reynolds, a tailor, demanded admission of his 8-year-old son Raoul to the new school. In an extensive review of the laws, the Kansas Supreme Court held for the Board of Education of Topeka on the basis that first-class cities were allowed to operate separate elementary schools. The court also argued that the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution did not supersede Kansas law.

1905: Special Legislation for Kansas City, Kansas

Mamie Richardson brought suit against the Board of Education of Kansas City in 1906 after she was not allowed to attend the morning classes at the high school to which white students had been assigned. This singular case came about after a fatal incident at the integrated high school influenced the Kansas Legislature of 1905 to pass a special act permitting Kansas City to operate separate high schools. The school board lost no time in enforcing separation by dividing each day into two sessions based on race, even as a new building, Wyandotte High School, was under construction. In ruling against Richardson the Kansas Supreme Court also upheld the constitutionality of this special legislation.

1908: Williams v. The Board of Education of Parsons (Kansas)

In the first-class city of Parsons, D. A. Williams won a narrowly based case on the issue of safety. In 1908 the Parsons board assigned all African American children to one of the four elementary schools. Williams, whose four children had attended school near their home, refused to have the children cross seven dangerous railroad tracks to reach the designated school. He was informed that his children and other African American students were required to attend a school designated for them.

The school was located more than a mile from the children’s home and was plagued by railroad traffic and train noises that disrupted the classroom. Mr. Williams filed legal action to remove his children from Lincoln School because of the dangers associated with travel to the school. The Kansas Supreme Court found that on the facts presented, Williams was entitled to relief, but left the door open for other separate school arrangements.

1916: Woolridge v. The Board of Education of Galena (Kansas)

Classrooms at East Galena Elementary School were integrated in grades 1 through 6. Because the school was overcrowded, the board of education called a meeting to develop a plan to reduce class size. The solution chosen was to hire an African American teacher, who would teach only African American children in one multigrade class.

To carry out this plan, representatives from Galena tried but failed to persuade the Kansas legislature to allow second-class cities to operate segregated schools. African American parents strongly objected to this change and filed suit to halt the board’s plans. Despite vocal intolerance, W. E. Woolridge and other parents won this 1916 case against the board of education, as the Kansas Supreme Court found that racial separation “was without authority of law” in the second-class city of Galena.

1924: Thurman-Watts v. The Board of Education of Coffeyville

African American attorneys and organizations factored in the 1924 challenge from Coffeyville, which had become a first-class city that legally operated separate elementary schools. Elijah Scott and R. M. Vandyne, African American attorneys from Topeka, represented Celia Thurman-Watts, whose daughter Victoria was denied admission to Roosevelt Junior High. Washington admitted both African American and white students, while only African American students attended Cleveland and only white students were designated to attend Roosevelt.

In questioning during depositions, Scott probed the allegiance of school board members to the Ku Klux Klan. The president of the school board admitted membership and another testified to past membership. Scott argued the broad issue of prejudice and noted the practical grounds of overcrowding in the Black schools. He won on the narrower grounds that the 9th grade was part of high school and separate high school education was not allowed except in Kansas City.

1927: Lum v. Rice

In 1924, a 9-year-old Chinese American named Martha Lum, daughter of Gong Lum, was prohibited from attending the Rosedale Consolidated High School in Bolivar County, Mississippi solely because she was of Chinese descent. There was no school in the district maintained for Chinese students, and she was forced by compulsory attendance laws to attend school.

Gong Lum filed suit, and a lower court granted the plaintiff's request to force the members of the Board of Trustees to admit Martha Lum. Gong Lum's case was not that racial discrimination as such was illegal but that his daughter, being Chinese, had incorrectly been classified as colored by the authorities. In Lum v. Rice, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that state’s rights and Plessy v. Ferguson applied to Asian American students, or as the court said, students of the “yellow race.”

1929: Wright v. The Board of Education of Topeka (Kansas)

Wilhemina Wright, an African American student at Randolph School, which was reserved for white students, was transferred to Buchanan School 20 blocks away. Eugene S. Quinton of Topeka represented Wilhemina’s father, George Wright, in his case. While it was agreed that Buchanan was as good a school as Randolph, the inconvenience and danger of a child walking to a school far from home did not allow equal access to education.

The decision came to rest on school busing. Wright lost this case, as the board provided bus transportation. In addition, as a first-class city, Topeka could operate separate elementary schools based on race.

1931: Roberto Alvarez v. the Board of Trustees of the Lemon Grove School District

On Jan. 5, 1931, Jerome T. Green, principal of the Lemon Grove Grammar School in Southern California, acting under instructions from the school trustees, stood at the door and admitted all pupils except the Mexican and Mexican American students. Principal Green announced that the Mexican children did not belong at the school and instructed them to attend a two-room building constructed to house Mexican children. The children left the school and returned home. Instructed by their parents, they refused to attend the socalled new school that had been built for them.

In the words of students of the time “It wasn’t a school. It was an old building. Everyone called it ‘La Caballeriza'” (the barnyard). The Mexican parents rallied together and (through the Mexican Consulate) acquired legal counsel and support. The school incident became a test case of the power of the District Attorney and the school board to create a separate school for Mexican children.

This case, Roberto Alvarez v. the Board of Trustees of the Lemon Grove School District, was the first successful school desegregation court decision in the history of the United States. The ruling succeeded in Lemon Grove because the Mexican American children were defined as white, and under California law they could not be separated from other white people. The families established the rights of their children to equal education, despite sentiment that favored not only segregation, but the actual deportation of the Mexican population in the United States. The ruling did not set a precedent for future school desegregation cases because the Board of Trustees lacked funds to appeal the case to a higher court.

1936: Murray v. Pearson

Donald Gaines Murray sought admission to the University of Maryland School of Law, but received a response stating that "the University of Maryland does not admit Negro students and your application is accordingly rejected."

After Murray’s appeal to the Board of Regents was rejected, Alpha Phi Alpha, the oldest Black fraternity in the U.S., decided to take up the case. The Baltimore NAACP’s Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall tried the case, using it as the first case to test Nathan Ross Margold's strategy to attack the “separate but equal” doctrine using the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. They argued that Maryland does not provide a “separate but equal” law school.

Laws vary from state to state, so a law school located in another state would not adequately prepare a Maryland attorney. The court agreed, and the circuit court judge issued a writ of mandamus ordering that Murray be admitted to the University of Maryland law school. The ruling was affirmed upon appeal by Maryland’s highest court, but never went to the U.S. Supreme Court.

1941: Graham v. The Board of Education of Topeka (Kansas)

The Graham case focused on the issue of whether 7th grade was part of high school. White children attended six grades in elementary schools, then three years in junior high schools. Black pupils continued to attend elementary schools for 7th and 8th grades, then transferred to Boswell or Roosevelt Junior High for 9th grade.

Tinkham Veale and William M. Bradshaw, representing Ulysses Graham’s parents, argued that the junior high schools were part of high school and that by not providing similar education for African Americans, these children were denied rights under the U.S. and Kansas Constitutions. The Kansas Supreme Court found that the refusal to permit 12-year-old Ulysses Graham to enroll in a junior high school was “discriminatory.”

1947: Mendez v. Westminster

When Gonzalo and Felicitas Mendez, two California farmers, sent their children to a local school, their children were told that they would have to go to a separate facility reserved for Mexican American students. The Mendez family recruited similarly aggrieved parents from local school districts for a federal court case challenging school segregation. Unlike the later Brown case, the families did not claim racial discrimination, as Mexicans were considered legally white (based on the preceding Roberto Alvarez v. the Board of Trustees of the Lemon Grove School District above), but rather discrimination based on ancestry and supposed “language deficiency” that denied their children their 14th Amendment rights to equal protection under the law.

On March 18, 1946, Judge Paul McCormick ruled in favor of the plaintiffs on the basis that the social, psychological, and pedagogical costs of segregated education were damaging to Mexican American students. The school districts appealed, claiming that the federal courts did not have jurisdiction over education, but the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ultimately upheld McCormick’s decision on April 14, 1947, ruling that the schools’ actions violated California law.

1949: Webb v. School District No. 90, South Park Johnson County (Kansas)

Population growth after World War II prompted construction of a new $90,000 South Park Elementary School near Merriam. The African American children were denied admittance to South Park School solely on the basis of race and color. When their children were turned away from the new South Park School, Webb and other parents took 39 children out of the poorly maintained, 90-year-old Walker School; hired Walker teacher Corinthian Nutter; and opened a home school.

Willingly risking further employment in the public schools, Nutter taught these children for over a year. African American parents found a staunch ally in Esther Brown, who supported and assisted them in their case. Through her urging, attorney Elijah Scott took the lead in bringing about the Webb case.

After the Kansas Supreme Court in 1949 ruled that equal facilities must be provided for all children, the board admitted Black children to South Park School. The issue of segregation per se was not part of the ruling, as facilities were so clearly unequal.

1954: Brown v. Board of Education

On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education. The case of Brown v. Board of Education as heard before the Supreme Court combined five cases: Brown itself, Briggs v. Elliott (filed in South Carolina), Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (filed in Virginia), Gebhart v. Belton (filed in Delaware), and Bolling v. Sharpe (filed in Washington, D.C.). All were NAACP-sponsored cases.

The Davis case, the only case of the five originating from a student protest, began when 16-year-old Barbara Rose Johns organized and led a 450-student walkout of Moton High School. The Gebhart case was the only one where a trial court, affirmed by the Delaware Supreme Court, found that discrimination was unlawful; in all the other cases the plaintiffs had lost as the original courts had found discrimination to be lawful. Decades of strategic planning and brave actions led to this historic ruling. A key figure in the history leading up to the Brown v. Board ruling is Charles Hamilton Houston, who established an accredited, fulltime (previously it was part-time) law program at Howard University. The focus was on civil rights to prepare lawyers, including Thurgood Marshall, to lead the fight against racial injustice. Houston argued precedent-setting cases and traveled throughout the South taking photos to document that separate was not equal.

1959: Clyde Kennard arrested after attempting to enroll at Mississippi Southern College

While this is not a school desegregation court case, Kennard’s case is an important part of the historical timeline of school desegregation. Korean War veteran Clyde Kennard put his life on the line in the 1950s when he attempted to become the first African American to attend Mississippi Southern College, now the University of Southern Mississippi, in Hattiesburg. Instead of being admitted, the state of Mississippi framed him on criminal charges for a petty crime and sentenced him to seven years of hard labor at Parchman Penitentiary. In response to a national campaign for his freedom, he was finally released as he was dying of cancer in January of 1963. Dick Gregory paid for his flight to Chicago for medical care, where he passed away less than six months later on July 4, 1963. Three Illinois high school students, their teacher, the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern Law School, and journalist Jerry Mitchell dedicated years to finally getting Kennard’s name cleared of the crime.

1962: Meredith v. Fair

In 1961 James Meredith was denied a transfer from Jackson State College (a segregated Black college) to the University of Mississippi — known as “Ole Miss,” and filed suit in federal court. In 1962 the 5th Circuit Court ruled that he was being denied admission because of his race in violation of Brown v Board of Education and ordered that he be admitted. In mid-September Meredith attempted to enroll as mandated by federal court order, but Gov. Barnett, who appointed himself registrar, refused to admit him three times. Violence flared across Mississippi as Black men, women, and children are attacked, beaten, and shot at. On the evening of Sept. 30, Meredith arrived at the Ole Miss campus accompanied by officials of the Department of Justice, who intended to enforce his registration the following morning. A crowd of more than 2,000 Klansmen, students, and townsmen attacked the marshals guarding Meredith with bricks, bottles, guns, and firebombs. The crowd murdered a reporter and another man. Pres. Kennedy called up Troop E of the Mississippi National Guard, but only 67 men responded. Finally, Kennedy sent in the United States Army to restore order. With tens of thousands of soldiers occupying Oxford, Meredith finally enrolled at Ole Miss on Monday, Oct. 1. Protected around the clock by armed guards, in August of 1963 he graduated with a BA in political science.

1969: Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education

Beatrice Alexander, mother of children, sued the Holmes County, Miss. School District, arguing that the District didn't complete any meaningful attempt to integrate its schools. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Alexander, writing that "The obligation of every school district is to terminate dual school systems at once and to operate now and hereafter only unitary schools." This meant that the previously set pace of “all deliberate speed” in the original Brown decision was no longer permissible.

In 1968, there were 771 white students in the county school system. Desegregation occurred in 1969, and that year the white student population decreased to 228. In 1970 no white students were enrolled in the public school system, with white children attending private segregated schools instead.