Comfort Food: A Lesson for Child of the Civil Rights Movement

Lesson by Paula Young Shelton

Food played an instrumental role during the Civil Rights Movement, bringing people together to plan, gain strength, and organize. Community members played an important role feeding volunteers. There are countless examples of this, such as the story shared by Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) veteran Rutha Mae Harris in an interview about her mother Katie B. Harris for Southern Foodways Alliance:

Outside of a handful of Black-owned restaurants, Albany [Georgia]’s diners and hotels were off limits to civil rights workers. Women like Ms. Harris’ mother stepped up. She knew how to set a welcome table. The house would be thick with the scent of candied yams and savory ham hocks in greens. When SNCC kids crowded the house at the end of the day, they emptied the serving bowls.

“Collard greens, cabbages, neck bones, fried chicken, cornbread, broccoli, potato salad,” Ms. Harris remembers. “Breakfast, it was bacon, grits, sausage, eggs, toast, milk, juice. Day in and day out until they were gone.”

Ms. Harris’ mother delighted in cooking for the SNCC workers. Her role wasn’t a hardship; it was an honor. “We were not a poor family,” Ms. Harris says. “My dad left us very well. My mother looked at it as her contribution because she knew that she was not gonna march. But she knew that her children would.”

As a child of the Civil Rights Movement myself, I have many fond memories of these kinds of meals and conversation. I included an example of this practice in the children’s book based on my own family history called Child of the Civil Rights Movement.

To bring this experience to my students (I teach 1st grade), I developed a lesson called “Comfort Food.”

It is designed to help students make a personal connection to the Civil Rights Movement and to recognize that people just like themselves came together as a community to fight against the injustices of segregation and discrimination.

The use of food in the story helps students to identify with the civil rights activists, unified by a common goal and engaging in the common practice of fellowship over a meal.

I have implemented this lesson in a variety of classrooms with much success. Students enjoy choosing their favorite foods to add to their menus and delight in inventing creative names for their foods. The lesson challenges them to demonstrate writing skills, practice alliteration, and identify adjectives, as well as recognize food groups. Examples of student menu items include change chicken, success salad, and cornbread of courage. The students especially enjoy experimenting with a variety of art materials to create their own plates of food.

The primary goal of this lesson is to inspire future social activists. As the students write their menus and design their plates, they are guided to view themselves as activists who must strengthen themselves and others to fight for justice and equality for all.

Grade Level: Kindergarten to 2nd grade

Time Required: One class period

Objectives

Recognize the role of community in social activism.

Make a personal connection with civil rights activists through family and food.

Identify food groups to create a menu.

Use alliteration to name menu items.

Describe food using adjectives.

Create a plate of foods out of various materials.

Materials

Child of the Civil Rights Movement by Paula Young Shelton and illustrated by Raul Colón

Art supplies

Additional Resources

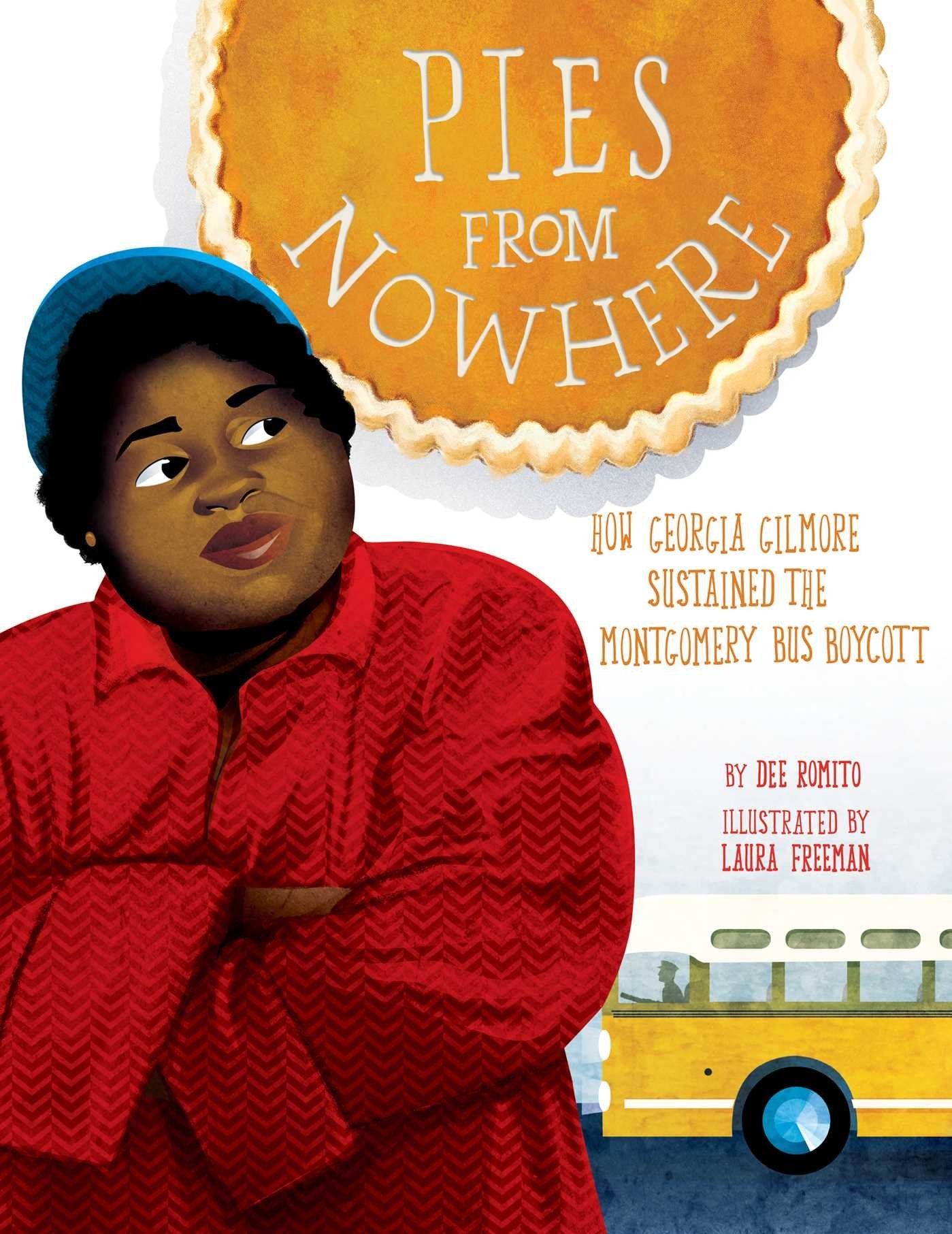

A related text for the classroom is Pies from Nowhere: How Georgia Gilmore Sustained the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a picture book by Dee Romito and illustrated by Laura Freeman. It tells the true story of Georgia Gilmore and the Club from Nowhere, a grassroots project to provide food and funds for the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Here is a description of Gilmore’s work by Premilla Nadasen in “Georgia Gilmore, Overlooked Activist of the Montgomery Bus Boycott” (Beacon Broadside):

“Some colored folks or Negroes could afford to stick out their necks more than others because they had independent incomes,” Gilmore explained, “but some just couldn’t afford to be called ‘ring leaders’ and have the white folks fire them. So when we made our financial reports to the MIA officers we had them record us as the money coming from nowhere. ‘The Club from Nowhere.’” Only Gilmore knew who made and bought the food and who donated money.

The underground network of cooks went door-to-door selling sandwiches, pies, and cakes, and collecting donations. The proceeds were then turned over to boycott leaders. Donations came from whites as well as Blacks.

That “was very nice of the people because so many of the people who didn’t attend the mass meetings would give the donation to help keep the carpool going.”

Here are additional stories about the role of the food during the Civil Right Movement from the website CRMvet.org as well as suggestions for additional reading.

Chuck Fager describes how the Black community in Selma welcomed and fed the out-of-town supporters in 1965:

In their humble houses the hosts plied their guests with the best meals they could afford, and many a stranger developed a lingering taste for collard greens and sweet potato pie in the course of a short stay. At the churches, a corps of intent, perspiring women labored all day and into each night frying heaps of chicken and baking large oblong pans full of warm, crumbly corn bread, for once cooking meals for white folks with all the pride anyone could ask for.

CORE and SCLC veteran Bruce Hartford describes food distribution on the Selma to Montgomery march:

A group led by Professor Elwyn Smith of the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary delivers food to the hungry marchers in a rented truck. Cooked by Black women laboring 16 hours a day in the kitchen at Green Street Baptist Church, the spaghetti, pork & beans, and coffee are ladled out to the marchers from new-purchased, galvanized steel garbage cans, while squares of corn bread are cut from large baking pans.

Bruce Hartford writes about the Brown Chapel kitchen in Selma, Alabama:

From before dawn to deep in the night the women in the church kitchens continue to serve fried chicken, greens, and cornbread to hungry protesters who grab a few winks of sleep on the church pews between mass meetings and their shift on the line. All of the women laboring at the hot stoves hour after hour are Black — except one. Nellie Washburn is the daughter of Nannie Washburn — 65 years old, Georgia born, child of white sharecroppers, a textile worker from age 7, a union organizer in the 1930s, a life-long “Red,” and a stalwart opponent of racism and exploitation. She, her blind son Joe, and her daughter Nellie answered Dr. King’s call. [Nannie Washburn explained]:

Well, my daughter, son, and I refused to eat the Jim Crow food, because there wasn’t anybody in the kitchen a cookin’ except Black women that was older than … as old as I was, and I was 65. … I went to Rev. Hollis and asked him. I said, “We not gonna eat ya Jim Crow food.” And he says, “Why?” I said, “My daughter has droved us, my son and I, down here, and I didn’t think I’d come to a Jim Crow kitchen.” And he said, “You a guest.” I said, “No, I’m not. I just one of ‘em.”

And he said then, “I don’t know nothin’ we could do about it.” I says, “Well, don’t you think the Black women’s been in the kitchen too long cookin’ for the white people?” And he commenced studyin’, and he said, “The only thing I can do is to let yo’r daughter go in the kitchen. I wouldn’t let you.” You know, I was 65.

Food was also an organizing issue. For example, when Black citizens in Leflore County, Mississippi began to try to register to vote, the White Citizens’ Council-controlled County Board of Supervisors stopped distributing the federal food aid that 22,000 people relied upon in what was known as the Greenwood Food Blockade. SNCC sent word to its supporters on college campuses and in Friends of SNCC chapters throughout the country — and people responded with donations. Bob Moses explains how the blockade backfired:

Whenever we were able to get a little something to give to a hungry family, we also talked about how they ought to register. The food was . . . identified in the minds of everyone as food for those who want to be free, and the minimum requirement for freedom is identified as registration to vote.

Find more stories in “Hostesses of the Movement: Everyday women fed a revolution” at the Southern Foodways Alliance.

© Paula Young Shelton. Printed with permission.