Brief Outline of the History of SNCC

Reading by Jenice L. View

The voting rights section of this book contains several lessons on SNCC. For more on the history of SNCC, see Charlie Cobb’s “The Story of SNCC” at snccdigital.org.

© Alabama Department of Archives and History, Jim Peppler Southern Courier photograph collection. Man and woman looking over a brochure for a political candidate before election day in Lowndes County, Ala. November 1966.

Dr. King’s book Stride Toward Freedom (1958) influenced four African American students in Greensboro, North Carolina in 1960 to conduct a sit-in at a local segregated Woolworth’s. The idea spread to Nashville, Tennessee and throughout the South. By fall 1960, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had formed at Shaw University under the facilitation of Ella Jo Baker, the executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). SNCC was established to bring order to the movement unleashed by the sit-ins. SNCC youth were highly resistant to adult manipulation and domination, a position that Ella Baker strongly encouraged. The young people of SNCC were determined to pick up the pace of racial justice by directly confronting institutional racism in their own way. Thanks to Baker’s network, they were introduced to key longtime organizers in the South, leading to intergenerational organizing.

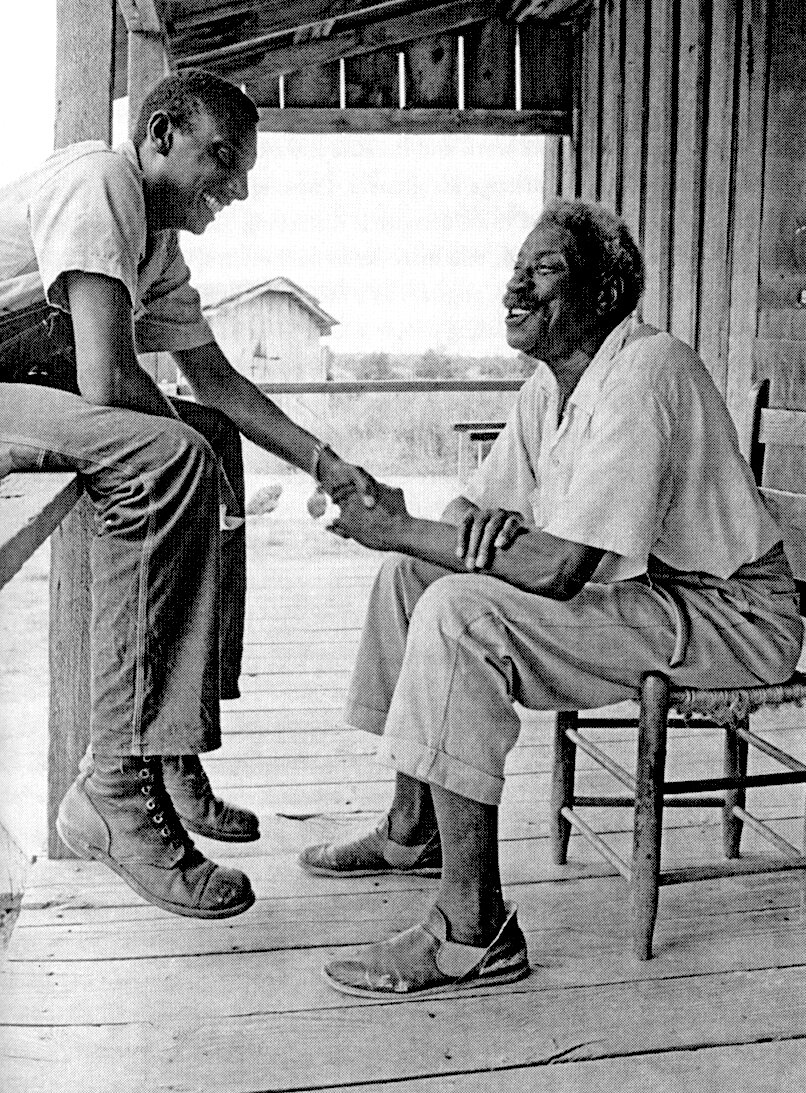

Stokely Carmichael canvassing in Lowndes County, Alabama. Library of Congress Look Magazine collection.

Stokely Carmichael canvassing in Lowndes County, Alabama. Library of Congress Look Magazine collection.

In its early phase, SNCC was dominated by followers of Christian Gandhism and nonviolent direct action was one of their primary tactics, leading to more sit-ins and to the Freedom Rides of 1961 and 1962. James Forman was the first executive secretary, trusted by the two factions within SNCC: the proponents of direct action and the proponents of voter registration. John Lewis, as the new chair of SNCC, spoke at the 1963 March on Washington. (Lewis went on to become congressperson from Georgia.) From the beginning, white students joined SNCC, including Bob Zellner, the grandson of a KKK member and the first white field secretary of SNCC.

By 1964, SNCC joined with NAACP, SCLC, and CORE to create Freedom Summer in Mississippi. Their objectives were to run 30 Freedom Schools throughout the state in order to register African Americans to vote and to form the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party as an alternative to the white-led state Democratic Party at the 1964 national convention. The strategy of voter registration grew in other states. By early 1967, Black voter registration rose from zero to 3,900 in Lowndes County, Alabama, a place widely known and feared for its racist brutality, and made nationally infamous 20 months prior by the murder of a white woman civil rights worker (Viola Liuzzo). Other whites from the North were murdered in their attempts to help African American southerners to vote, raising the profile of SNCC and the strategy of voter registration as direct action in a racist atmosphere. However, countless African Americans from the rural South were murdered; beaten; harassed; fired from jobs; and had their homes, churches, and businesses firebombed with no justice served and no media attention.

In 1966, Stokely Carmichael became chair on a Black Power platform, followed by H. Rap Brown in 1967. As SNCC became more militant, the FBI increased its efforts to infiltrate, destabilize, and destroy the organization and its leaders. The controversies among its members also heightened. Rifts deepened concerning the use of violence in achieving racial justice and the roles of whites, of women, and of African Americans from the North who were new to SNCC. In 1970, SNCC disbanded, partly due to its original intentions to avoid turf battles, to avoid creating a perpetual organization, and to foster local leadership strong enough to put SNCC “out of a job.”

SNCC is credited with many of the most innovative and effective fronts of the Civil Rights Movement, including:

Youth leadership that organized and empowered existing leaders regardless of age.

Nonviolent direct action (sit-ins, Freedom Rides, etc.).

Voter registration, freedom elections, freedom days (whole days of organizing voter registration).

Strengthening the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by forcing the inclusion of Section 5, which banned arbitrary state laws, and winning a Supreme Court lawsuit that broadened the scope of Section 5 (Whitley v. Johnson).

Use of popular education and Freedom Schools.

Political party formation and changes in rules regarding the selection of delegates (as a result of the reforms, half of all party delegates must be women).

Winning the right to vote for people who cannot read.

Women’s leadership.

Investing in long-term development of local leaders rather than in short organizing campaigns.

Promotion of Black nationalism and Black Power.