At the River I Stand: The 1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike and the Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Reading by California Newsreel

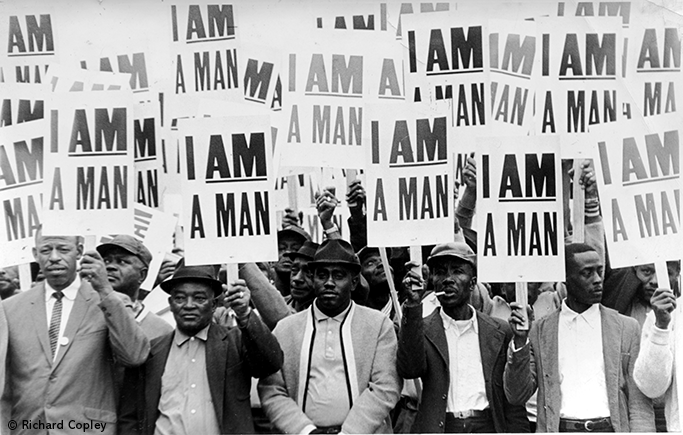

Striking members of AFSCME Local 1733 hold signs whose slogan symbolized the Memphis sanitation workers' 1968 campaign. At center is James Riley. To his right is Hubbell Clark. To Riley's left is a man known as "Jumping Jack." © Richard Copley

The documentary film At the River I Stand, produced by David Appleby, Allison Graham, and Steven John Ross (available from California Newsreel) skillfully reconstructs the two eventful months that transformed a strike by Memphis sanitation workers into a national conflagration, and disentangles the complex historical forces that came together with the inevitability of tragedy at the death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

This 58-minute documentary brings into sharp relief issues that have only become more urgent in the intervening years: the connection between economic and civil rights, debates over strategies for change, the demand for full inclusion of African Americans in American life, and the fight for dignity for public employees and all working people.

In the 1960s, Memphis’s 1,300 sanitation workers formed the lowest caste of a deeply racist society, earning so little that they qualified for welfare. In the film, retired workers recall their fear about taking on the entire white power structure when they struck for higher wages and union recognition.

But local civil rights leaders and the Black community soon realized the strike was part of the struggle for economic justice for all African Americans. Through stirring historical footage we see the community mobilizing behind the strikers, organizing mass demonstrations and an Easter boycott of downtown businesses. The national leadership of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) put the international union’s full resources behind the strike. One day, a placard appeared on the picket lines that in its radical simplicity summed up the meaning of the strike: “I am a man.”

In March, Martin Luther King Jr. came to Memphis as part of his Poor People’s Campaign to expand the civil rights agenda to the economy. The film recreates the controversies between King’s advisors, local leaders, and younger militants — debates that led to open conflict. When young people engaged in a violent confrontation with the brutal Memphis police, King left.

King and the nation realized that his leadership and nonviolent strategy had been threatened. King felt obliged to return to Memphis to resume a nonviolent march despite the by-now feverish racial tensions. The film captures the deep sense of foreboding that pervaded King’s final “I have been to the mountaintop” speech. The next day, April 4, 1968, he was assassinated.

Four days later, thousands from Memphis and around the country rallied to pull off the nonviolent march. The city council caved and granted most of the strikers’ demands. Those 1,300 sanitation workers had shown they could successfully challenge the entrenched economic structure of the South.

Endemic inner-city poverty, attempts to roll back gains won by public employees, and the growing gap between the rich and the rest of us make clear that the issues Martin Luther King Jr. raised in his last days have yet to be addressed. At the River I Stand succeeds in showing that the causes of (and possibly the solutions to) our present racial quandary may well be found in what happened in Memphis.

Reprinted with permission from California Newsreel. Find out how to stream the entire film at newsreel.org.

Related lesson: “Remembering the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike: A Collaborative Mural.”