Radical Equations: The Algebra Project Drawing on the Past: The Roots of Our Movement

Reading by Robert P. Moses and Charles Cobb Jr.

The Algebra Project, founded in 1982 by SNCC veteran Bob Moses, uses math literacy as an organizing tool, much as the Citizenship Schools focused on reading and writing in the 1950s. As is explained at the SNCC Legacy Project website, “The operating principle is that just as people at the bottom levels of society in Mississippi require access to the right to vote to gain political power and access to full U.S. citizenship, young people need access to algebra to gain full citizenship in the 21st Century.”

In this excerpt from the book Radical Equations, Moses describes the thinking behind the Algebra Project and the focus on youth. Moses led the Algebra Project until his death in July of 2021. The work continues in school districts around the country and with an annual conference. Learn more at algebra.org.

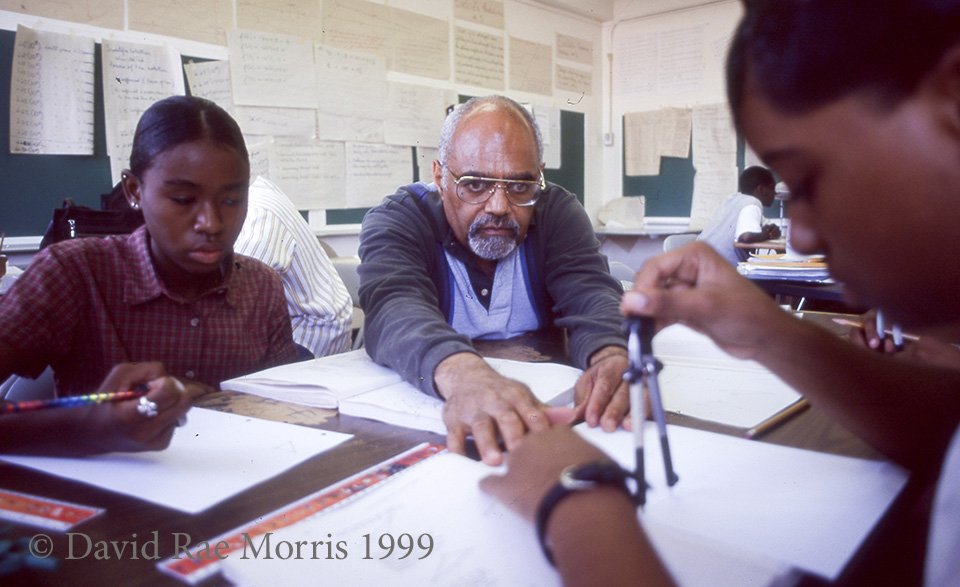

Bob Moses teaching at Lanier High School in Jackson, Mississippi in 1999. © David Rae Morris

The Algebra Project is first and foremost an organizing project — a community organizing project — rather than a traditional program of school reform. It draws its inspiration and its methods from the organizing tradition of the Civil Rights Movement. Like the Civil Rights Movement, the Algebra Project is a process, not an event.

Two key aspects of the Mississippi organizing tradition underlie the Algebra Project: the centrality of families to the work of organizing, and organizing in the context of the community in which one lives and works. As civil rights workers in Mississippi, we were absorbed into families as we moved from place to place with scarcely a dollar in our pockets, and this credential being one of the community’s children negated the white power structure’s efforts to label us “outside agitators.” In this way we were able to sink deep roots into the community, enlarging and strengthening connections in and among different communities, absorbing into our consciousness the community’s memories of “where we have been,” forcing us to our own understanding of our collective experience.

We are struggling to frame some important questions: Is there a way to talk with young people today as Amzie Moore and Ella Baker did with us in the 1960s? Is there a consensus for young Blacks, Latinos, and poor whites to tap into that will drive such a literacy effort? What price must they pay to wage such a struggle?

Like Ella Baker, we believe in these young people, that they have the energy, the courage, and the hope to devise means to change their condition. Although much concern about the education of African-American young people is voiced today, I am frequently asked why I have turned to teaching school and developing curriculum — teaching middle school and high school no less. There is a hint of criticism in the question, the suggestion that I am wasting my time, have abandoned efforts at attempting real, meaningful social change. After all, in the end, such work “merely” leads to youngsters finding a comfortable place in the system with a good job. Nothing “radical” about that, I am told. This is a failure to understand what actually is “radical,” so it might be useful to repeat what Ella Baker posits as necessary to the struggle of poor and oppressed people: “It means facing a system that does not lend itself to your needs and devising means by which you change that system.”

The key word here is you. Our efforts with our target population is what defines the radical nature of the Algebra Project, not program specifics. To make myself very, very clear, even the development of some sterling new curriculum — a real breakthrough — would not make us happy if it did not deeply and seriously empower the target population to demand access to literacy for everyone. That is what is driving the project. What is radical about the Algebra Project is the students we are trying to reach and the people we work with to drive a broad math literacy effort the Black and poor students and the communities in which they live, the usually excluded. Ella’s words finally mean, whether for voting rights or economic access, “You who are poor and oppressed: your need, you must make change. You must fashion a struggle.” Young people finding their voice instead of being spoken for is a crucial part of the process. Then and now, those designated as serfs are expected to remain paralyzed, unable to take an action and unable to voice a demand — their lives dependent on the goodwill and good works of others. We believe the kind of systemic change necessary to prepare our young people for the demands of the 21st century requires young people to take the lead in changing it.

Portrait of Ella Baker by Phoebe Rotter of Black Lives Matter-Greater Burlington. Photo: Deborah Menkart

These are radical ideas the way that 40 years ago constructing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) so that sharecroppers and day workers could have a voice was radical. What made it radical was the work, the effort, at encouraging this group to empower itself. This was Ella Baker’s great lesson, and still a touchstone for us today: that the target population should also make a demand instead of just having their needs advocated by well-intentioned “radical” reformers. You might say that it radicalizes radicalism. That’s what we learned in Mississippi, that it is getting people at the bottom to make of Black Lives Matter demands, on themselves first, then on the system, that leads to some of the most important changes. They have to find their voices. No matter how great Martin Luther King Jr. was, he could not go and challenge the seating of the Mississippi Democrats at Atlantic City. He could advocate for them and support them, but he could not lead the challenge. The only people who could do that were the people from Mississippi. And people will not organize that kind of seminal effort around somebody else’s agenda. It’s got to be internalized — this is our agenda.

There had been advocates for civil rights long before SNCC and CORE field secretaries arrived in Mississippi. Indeed, the 1954 Supreme Court decision was one important victory won by civil rights advocates. And perhaps because it was primarily won by advocates, it proceeded “with all deliberate speed.” No one disputes the importance of such victories, but, nonetheless, it was when sharecroppers, day laborers, and domestic workers found their voice, stood up, and demanded change, that the Mississippi political game was really over. When these folk, people for whom others traditionally had spoken and advocated, stood up and said, “We demand the right to vote!” refuting by their voices and actions the idea that they were uninterested in doing so, they could not be refused, and the century-long game of oppression through denial of the political franchise ended.

So to understand the Algebra Project you must begin with the idea of our targeted young people finding their voice, as sharecroppers and day laborers, maids, farmers, and workers of all sorts found theirs in the 1960s. Of course there are differences between the 1960s and what the AP is doing now. For one, the time span between the start of the sit-in movement and the challenge by the MFDP in Atlantic City was incredibly brief, sandwiched between two presidential elections (Kennedy-Nixon and Johnson-Goldwater). When I look back, it feels like 20 years folded into four; I still can hardly believe how short a time period that was. Math literacy, however, will require a longer time frame. There is a steep learning curve, and what we’re looking at with the AP is something evolving over generations as math literacy workers/organizers acquire the skills and training through study and practice and begin tackling the system. Young people, however, may speed this up as youth clearly did in the Civil Rights Movement. And, whereas the right to vote campaign took place in the Deep South, the math literacy problem is throughout the entire nation.

Yet to understand the Algebra Project, you need to understand the spirit and the crucial lessons of the organizing tradition of the Civil Rights Movement. In Mississippi, the voiceless found their voice, and once raised, it could not be ignored. Organizers learned to locate the vast resources in communities that seemed impoverished and paralyzed at first glance. The lessons of the movement in Mississippi are exactly the lessons we need to learn and put into practice in order to transform the education of our children and their prospects for the future. As with voting rights four decades ago, we have to flesh out a consensus on math literacy. Without it, moving the country into systemic change around math education becomes almost impossible. You cannot move this country unless you have consensus. The country’s too big, too huge, too diverse, too confused. That’s part of what we learned in Mississippi. We learned it on the ground, running.

© 2001 Algebra Project. Robert P. Moses and Charles Cobb Jr., Radical Equations: Math Literacy and Civil Rights (Beacon Press, 2001). Reprinted permission of Beacon Press.