Meet Medgar Evers: Introduction to the Southern Freedom Movement

Lesson by Deborah Menkart and Jenice L. View

Medgar Wiley Evers was one of Mississippi’s most impassioned activists, orators, and visionaries for equality and against brutality. However, many students learn little about his life and legacy in textbooks. Therefore, Teaching for Change prepared this lesson to introduce students to his work and to inspire them to learn more. Designed as a pre-reading activity, the lesson also provides a scaffold for students of the people, places, and issues in Evers’ life.

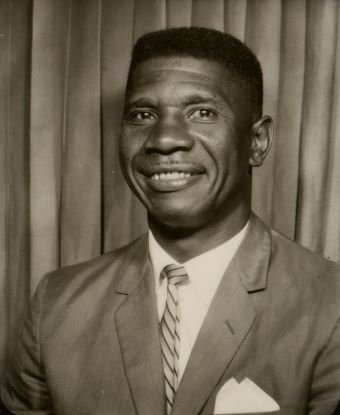

Medgar Evers. Photo: Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Grade Level: Grades 7+

Time Required: Two class periods

Objective

Students will be introduced to the rich story of Medgar Evers’ life and be motivated to learn more. The brief lesson presents:

Medgar Evers in a context of organizations and communities

Medgar Evers as an organizer and advocate

The people who influenced Medgar Evers and those whom he influenced

The legacy of Medgar Evers

Materials

Interview sheet. One per student.

Roles or brief bios. One per student.

Because this is an introductory lesson, the bios are short, reader-friendly, and reflect the range of Evers’ work and contacts. It is our hope that these short bios interest students in learning more.

James and Jessie Evers

Medgar Evers as a child

Medgar Evers as college student

Medgar Evers in NAACP

Ernst Borinski

C.C. Bryant

Youth Councils – (Hattiesburg)

Sovereignty Commission

Tougaloo Nine

Mamie Till Mobley

Theron Lynd

Clyde Kennard

Dorie and Joyce Ladner

Ruby Hurley

Amzie Moore

Amos Brown

Jim Thames

Fannie Lou Hamer

Anne Moody

Theodore Roosevelt Mason (TRM) Howard

Hollis Watkins

James Meredith

Dr. Gilbert Mason

John R. Salter

Aaron Henry

Minnie White Watson

Clarion Ledger newspaper

White Citizens’ Council

Governor Ross Barnett

Pre-Reading

We recommend that the teacher learn as much as possible about the life and work of Medgar Evers prior to using this lesson. Here is a brief bio and links to books and film clips.

Brief Bio of Medgar Evers

Born July 2, 1925, in Decatur, Mississippi, Evers was one of four children born to James and Jesse Evers. Evers spent the most time with older brother Charles, whom he idolized because Charles protected him, taught him to fish, swim, hunt, box, wrestle, and to think about the world and their unequal, segregated schooling. In addition, Evers saw and witnessed acts of raw violence against Blacks; his parents and brother could not shield him from the realities of a society built on racial discrimination.

The United States Army inducted Evers in 1942. Though typical at the time, racial segregation in the military only served to anger Evers. By the end of the war, Evers was among a generation of Black veterans committed “to return [home] fighting” for change. The initial “fight” for Evers was to register to vote as an affirmation of citizenship. In the summer of 1946, along with his brother, Charles, and several other Black World War II veterans, Evers registered to vote at the Decatur city hall. But on Election Day, the veterans were prevented by angry whites from casting their ballots.

The experience only deepened Evers’s conviction that the status quo in Mississippi had to change. By 1954, Evers began an 8-year career as the Mississippi state field secretary for the NAACP. His organizing focused on voter registration, educational equity, the creation of NAACP Youth Councils, and investigations of racist murders. As a result, the number of NAACP members who boycotted and agitated for justice doubled in Mississippi. Assassinated in the driveway to his house in 1963, his murderer was not brought to justice until 1994. Thanks to Medgar Evers and other activists, the groundwork was laid for the Mississippi freedom and voting rights struggles of the 1960s and 1970s.

Procedure

Cut the roles on the dotted lines.

Distribute roles so that each student has one (or two if needed so that each role is included.)

Explain to students: “You will have a chance to meet people connected to the life of Medgar Evers. Three of you will be Medgar Evers himself at different periods in his life. You will interview each other, in role, using a set of questions on an interview sheet.” Ask them to read their role two or three times so that they can prepare to step into that person’s shoes.

Provide each student a copy of the interview questions. Their assignment is to circulate through the classroom, meeting other individuals from Medgar Evers’ life. They should use the questions on the sheet to talk with others about Evers and to complete the questions as fully as possible. They must find a different individual to answer each of the six questions. As Bill Bigelow explains in a lesson using this format in a lesson on the U.S.-Mexico War, “Remind students that this is not a race; the aim is to spend time hearing each other's stories, not just hurriedly scribbling down answers to the different questions.”

Model a sample interview with a student volunteer to demonstrate an encounter between two of the individuals.

Provide time for students to circulate throughout the class, interview each other, and fill out responses to the interview questions.

Bring everyone back together.

Have students talk in small groups (three to four students each) about the question: “Why was Medgar Evers an effective leader?”

Have groups summarize their response in two sentences to share with the group verbally or post on a flip chart.

Ask the students some of the following possible questions:

What were some similarities and differences in your responses?

What questions do you still have about Medgar Evers?

How are the efforts and work of Medgar Evers still felt today?

Encourage students to continue learning, discussing, and debating about the life and legacy of Medgar Evers and the Mississippi Freedom Movement.