Uncovering the Movement: A Staff Development Seminar

Lesson by Alana D. Murray

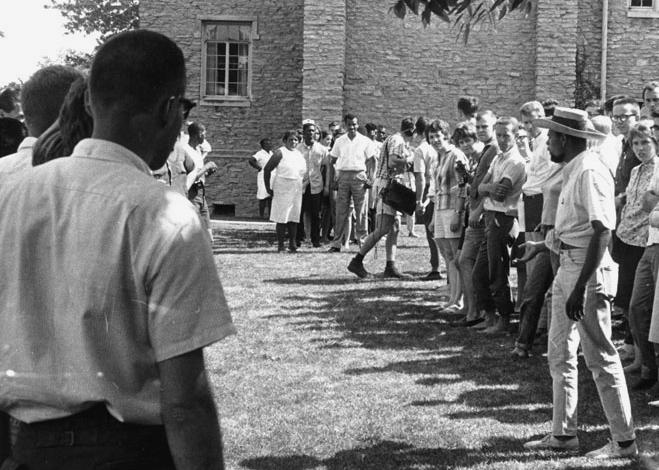

Freedom Summer volunteers gathered with SNCC field secretary Cordell Hull Reagon (on right, wearing a hat) for instruction in nonviolent self-defense at the second SNCC Orientation Session held at Case Western College for Women in Oxford, Ohio, between June 22 and 27, 1964. In the center left of the picture wearing a sleeveless dress, stands Fannie Lou Hamer. Herbert Randall Freedom Summer photographs, McCain Library and Archives, University of Southern Mississippi.

This workshop is designed to give teachers and other school staff a chance to examine their own understanding of the Civil Rights Movement and to consider the impact of the traditional narrative on students. Part One of the workshop engages participants in critical examination of the traditional narrative, while Part Two engages participants in a variety of approaches that can be used in the classroom.

Grade Level: Teaching staff

Time Required: Two to three hours is ideal for this workshop. If only one hour is available, then the session can be limited to Part One.

Materials

“A View from the Trenches” by Charles Payne.

“The Politics of Children’s Literature” by Herbert Kohl. (If time is limited for the workshop, divide this reading into subsections and have the participants read different sections.)

Traditional vs. Historically Accurate Narratives Chart. (Make enough copies for every four participants. Also be prepared to display the handout on a whiteboard or flipchart.)

Facilitator Reference: Traditional vs. Historically Accurate Narratives Chart Possible Responses

Procedure

Ask the participants, working in pairs, to list the most important things they can remember that they were taught about the Civil Rights Movement. This can include when it started, why did it start, who started it, important events, etc. Stress that they should list only information that they were taught in elementary or secondary school, not what they learned later in college or from their family.

After a few minutes, have them share some of the items from their lists and write them on the board. They will most likely be points from what is considered the “traditional narrative.” Explain that with few exceptions, this is the story that most of us have learned ever since we first heard about “I Have a Dream” in 1st grade.Have the participants break into groups of four. Distribute the readings and Traditional vs. Historically Accurate Narratives Chart. In each group, ask that two people read the “A View from the Trenches” by Charles Payne and the other two read “The Politics of Children’s Literature” by Herbert Kohl. Explain that once they have finished reading, they should fill out as much of the Historically Accurate Narrative column in the Traditional vs. Historically Accurate Narratives Chart as possible. They can rewrite the current sentences or simply list information that is missing or misrepresented. You can give them an example for the first sentence.

Have groups share some of the information they have found.Explain that now you will explore why this matters. In these days, with so much material to cover each school year, a more in-depth version of history seems like a luxury — so is it really necessary?

Remind participants that the Civil Rights Movement is probably the most commonly taught story about civic engagement and social change, so we need to examine what children are learning about their own role in a democracy from the Movement. Present the Traditional vs. Historically Accurate Narratives Chart. The facilitator’s reference has some possible responses in italics. Ideally the analysis should come from the group.

Here are a few examples from the Facilitator’s Guide:

Traditional Narrative

Traditionally, relationships between the races in the South were oppressive.

Historically Accurate Narrative

Racism was not limited to the South, nor did it exist in a vacuum. In reality, racism existed and exists throughout the United States, and is not just based on “relationships,” but on institutional power and policies. One could say instead, “Racism permeated and was institutionalized by almost every major institution in the United States, both public and private, including federal and local governments, the media, religious institutions, labor unions, etc.

Martin Luther King Jr. led the Civil Rights Movement.

The Movement consisted of many leaders and hundreds of thousands of activists. Martin Luther King Jr. played a critically important role as a powerful spokesperson, but he was not the leader nor the initiator of the Movement.