Transportation Protests: 1841 to 1992

Reading by Julian Hipkins III and David Busch

People in the United States have long relied on public transportation to get to jobs and appointments, go shopping, visit family and friends, and enjoy freedom of movement. As a public good paid for by taxpayer dollars, or a private company subsidized by public funds, local buses and trains have been subject to the same equal access expectations as other public goods. All residents of a community have a constitutional right to equal protection under the law, including the right to ride on public conveyances. However, the struggle for the racial desegregation of transportation has a long history, as powerful whites claimed to control the freedom of movement of people of color.

Below are some key individuals and organizations who took a stand against segregated transit to afford freedom of movement to all. Countless more examples can be found in the book Traveling Black: A Story of Race and Resistance by Mia Bay.

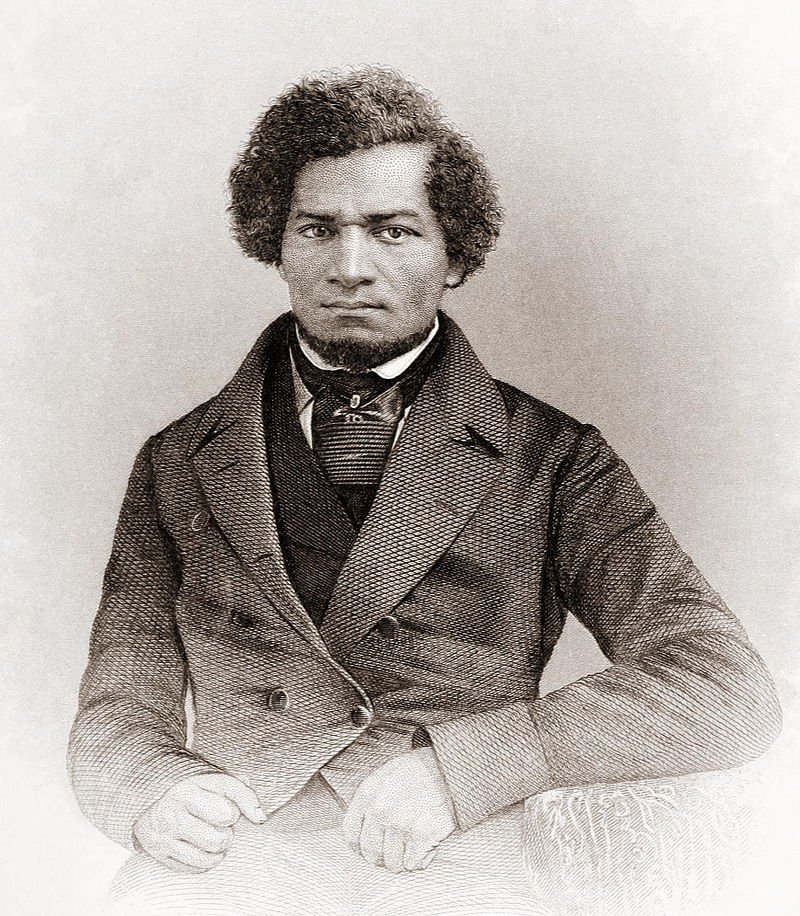

1841: FREDERICK DOUGLASS

On September 29, 1841, Frederick Douglass and his friend James N. Buffum entered a train car reserved for white passengers in Lynn, Massachusetts. When the conductor ordered them to leave the car, they refused. Douglass’ and Buffum’s actions led to similar incidents on the Eastern Railroad. Widespread organizing led Congress to grant equal rights to Black citizens in public accommodations with the Civil Rights Act of 1875. However, the Supreme Court overturned this victory in 1883, declaring it unconstitutional. Learn more.

1854: ELIZABETH JENNINGS GRAHAM

On July 16, 1854, Elizabeth Jennings Graham, a 24-year-old schoolteacher, fatefully waited for the bus in New York City. Some buses bore large “Colored Persons Allowed” signs, while all other buses were governed by a rather arbitrary system of passenger choice. When Jennings opted for a bus without the “Colored Persons Allowed” sign, the conductor told her to get off. When she insisted on her right to stay, he took hold of her by force to expel her. Learn more.

1863: CHARLOTTE BROWN

Months after San Francisco’s horse-powered streetcar companies first dispatched their streetcars (with orders to only accept white passengers), African American citizens began to directly challenge this discrimination. On April 17, 1863, Charlotte Brown, a young African American woman from a prominent family, boarded a streetcar and was forced off. Determined to assert her rights, Ms. Brown boarded streetcars twice more and was twice more ejected by the year’s end. Each time she began a legal suit against the company.

In May 1863, William Bowen, an African American, was stopped from boarding a streetcar. He brought a civil suit and a criminal assault suit. Their legal actions came after the African American community’s successful campaign to remove the state’s ban on court testimony by African Americans. Lifting this ban opened the legal system to challenges by African American men and women in the state.

Mary Ellen Pleasant, a longtime foe of segregation and leading supporter of John Brown, brought suit against San Francisco streetcar companies when she was ejected in 1866, and after two years of court battles the lines were desegregated. Learn more.

1865: OCTAVIUS VALENTINE CATTO

On May 17, 1865, just one month after the end of the Civil War, activist, educator, and soldier Octavius Catto refused to leave his seat when ordered to do so on a trolley car in Philadelphia during a campaign to desegregate public transportation in the city. The conductor ran the trolley off the tracks and detached the horses that were pulling it, leaving it inoperable. Maintaining his civil disobedience, Catto remained seated on the trolley throughout the night. With the help of Congressmen Thaddeus Stevens and William D. Kelley, Catto worked to pass a bill prohibiting segregation on transit systems in Pennsylvania.

In October 1871, at the age of 32, Catto was on his way to vote when he was killed by a white man. In 2017, a statue was erected in his honor on the southside of Philadelphia's City Hall. Learn more.

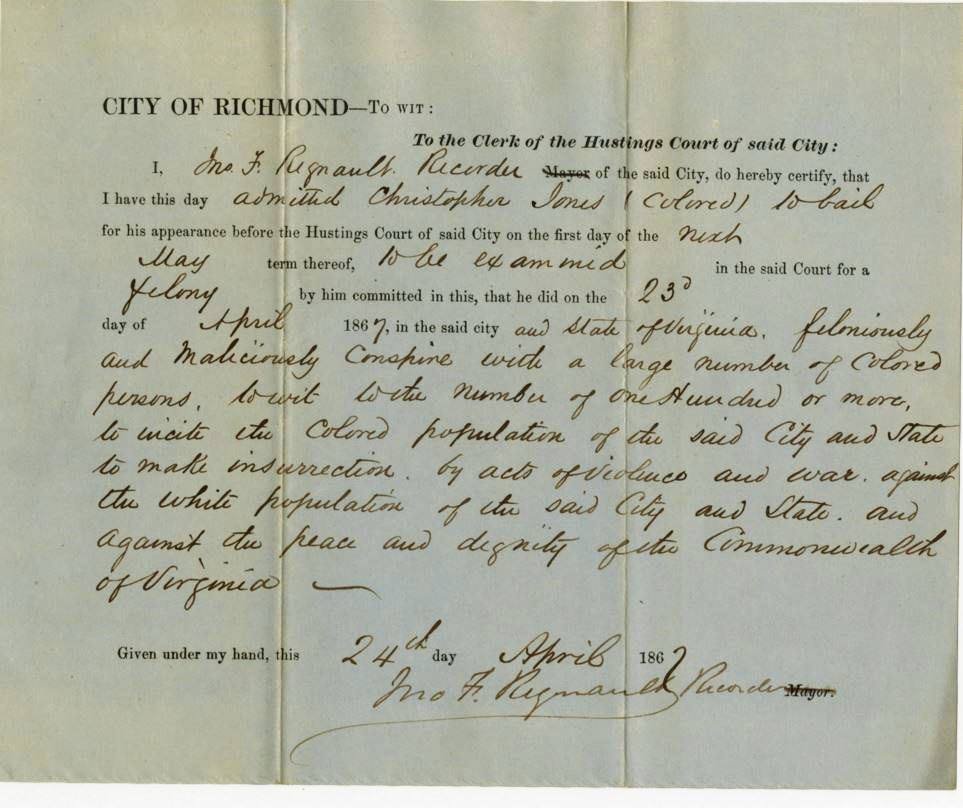

APRIL 24, 1867: RICHMOND STREETCAR PROTEST

On April 24, 1867, African Americans in Richmond, Virginia organized Reconstruction era protests against the privately operated company that refused to allow them to ride its horse-drawn streetcars. Christopher Jones had tried to board a streetcar and was arrested for disturbing the peace after a large crowd assembled to support his insistence that, having bought a ticket, he was entitled to ride the streetcar.

African Americans in the crowd reportedly shouted, “Let us have our rights,” and “We will teach these d—d rebels how to treat us.”

Jones was indicted for “feloniously and maliciously” conspiring to “incite the Colored population of the said City and State to make insurrection by acts of violence and war against the white population.”

On May 18, the court issued a “nolle prosequi,” or an order not to prosecute his case.

This description is from Remaking Virginia: Transformation Through Emancipation.

Learn more from the book Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship in the Era of Plessy v. Ferguson and at the Zinn Education Project.

1868: KATE BROWN

Kate Brown was an African American Senate employee in charge of the ladies’ retiring room. As described at Senate.gov: On February 8, 1868, Brown pulled out her ticket and prepared to board a train, to return to Washington from Alexandria, Virginia. As she stepped aboard, she was accosted by the rail line’s private police officer, who angrily told her she must enter the other car. “This car will do,” Brown replied quietly. At that point, as she later told a Senate investigating committee, “the policeman ran up and told me I could not ride in that car. . . he said that car was for ladies.” Of course, Kate Brown was a lady, but she was also African American.

Not deterred, Brown responded: “I bought my ticket to go to Washington in this car. . ., before I leave this car I will suffer death.” A violent altercation ensued. Reportedly, the police officers employed by the railroad physically ejected Brown from the train, throwing her onto the platform. Continue reading.

Read a more detailed account in “Winning the Right to Ride: How D.C.’s streetcars became an early battleground for post-emancipation civil rights” by Kate Masur via Slate.

1870-1871: FREEDOM’S MAIN LINE: LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY

On October 30, 1870, three men outside the Quinn Chapel in Louisville, Kentucky, made their way toward the trolley stand at Tenth and Walnut on the Central Passenger line. When the trolley stopped, each climbed aboard the near-empty car, dropped a coin in the fare box and took a seat.

It would have been a routine occurrence — three men catching a ride home after church on a Sunday afternoon — had the passengers been white residents of Louisville. But they were African American. And for Black city dwellers, riding a trolley was no ordinary act. It was a challenge to the entire social order. Learn more.

1884: IDA B. WELLS

On May 4, 1884, antilynching activist Ida B. Wells was asked by the conductor to move from her seat in the ladies’ car to the smoking car at the front of the train. She refused and was ordered to get off the train. Again, she refused to leave her seat that she had paid for as a customer. Wells was then forcefully removed from the train and, when the situation ended, the other passengers — all whites — applauded. When Wells returned to Memphis, she immediately hired an attorney to sue the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad Company. She won her case in the local circuit courts, but the railroad company appealed to the Supreme Court of Tennessee, which reversed the lower court’s ruling. Learn more.

1892: THE CRUSADER AND THE COMITÉ DES CITOYENS

On June 7, 1892, Homer Plessy bought a first-class ticket on the East Louisiana Railway. He took a vacant seat in a coach reserved for white passengers. This act was planned with the help of the Comité des Citoyens and the railroad company, which had opposed the law on the grounds that it would require the purchase of more rail cars. The hope was to bring a case to court that would allow African Americans to ride wherever they pleased. When Plessy was ordered to leave, he disobeyed and was thrown off the train, arrested, and thrown in jail. He was charged with violating the Louisiana segregation statute of 1890. The Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that the Louisiana law did not violate the 13th and 14th Amendments, ushering in the legal doctrine of “separate but equal” and Jim Crow Laws. Learn more.

1904: MAGGIE LENA WALKER

Maggie Lena Walker was an African American entrepreneur and civic leader who broke traditional gender and discriminatory laws by becoming the first woman — white or Black — to establish and become president of a bank in the United States: the Saint Luke Penny Savings Bank in Richmond. In 1904, Walker was one of the organizers of a boycott that protested the Virginia Passenger and Power Company’s policy of segregated seating on Richmond streetcars. The boycott was so successful that the company went out of business within the year. Learn more.

1906: BARBARA POPE

Barbara E. Pope (1854–1908) was a high school teacher, fiction author, and active in the Niagara Movement. According to research by Jennifer Harris, as reported in The Washington Post, Pope “boarded at Union Station and saw the ‘colored’ compartment was cramped and its seats faced backward. She took a seat in the main compartment instead. After they crossed the Potomac into Virginia, a white conductor came and said she had to move. She refused. He threatened her with arrest. She refused again. . . . Pope was arrested and tried for ‘violating the separate car law of the State of Virginia’ and fined $10 plus court costs.” She appealed and filed for damages in federal court. Read more.

1937: CONGRESSMAN ARTHUR WERGS MITCHELL

On April 21, 1937, Illinois congressman Arthur Wergs Mitchell, was told to move to the section of the train designated for African American passengers, in accordance with the Arkansas Separate Coach Law of 1891.

Under threat of arrest, Mitchell moved to the designated area and filed a lawsuit once he returned to Illinois.

The ICC dismissed the complaint, stating that “the discrimination and prejudice was plainly not unjust or undue.” He also lost on appeal to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, which stated that “the small number of colored passengers asking for first-class accommodations justified an occasional discrimination against them because of their race.”

Mitchell appealed that ruling directly to the U.S. Supreme Court, where he presented oral arguments himself. The Supreme Court ruled in his favor on April 28, 1941 in Mitchell v. United States et al. However, his political career in Chicago was over because of his having angered the white political establishment. Read more at the Zinn Education Project.

1938: ELLEN HARRIS

In Durham, North Carolina on February 12, 1938, a bus driver asked Ellen Harris to move to the back of the bus when a white passenger got on board. She refused, but offered to get off the bus if her fare was refunded. Instead of refunding her fare, the bus driver had Ms. Harris arrested for violating segregation laws. Ms. Harris, represented by two Black attorneys, Caswell Jerry Gates and Edward Richard Avant, was tried and convicted in Recorder’s Court and fined $10.00. She appealed her case to the Superior Court, where she received a trial by jury and was again convicted for “unlawfully and willfully” occupying a seat. Gates and Avant immediately appealed her case to the North Carolina Supreme Court, where Judge J. Carson reversed her criminal conviction. He wrote “we do not think the defendant intended to willfully violate the provisions of this act.” Ellen Harris did not stop there.

One month after being found innocent of the criminal charges, Ms. Harris and her attorneys filed a $15,000 civil lawsuit against Durham Public Services Company. The record shows that she settled her case with Durham Public Services for an undisclosed amount. Learn more.

1940: PAULI MURRAY AND ADELENE MCBEAN

In late March 1940, Pauli Murray and Adelene McBean boarded an old bus headed for Durham, North Carolina. For months, Murray and McBean had discussed how they could effectively challenge racial segregation. Seated in the back of the bus over the wheel hub, the two young women suffered from each bump and decided to move to the middle of the bus. The driver told them to move back where they were previously seated. The two women refused, and, after a debate with the driver and local police, were arrested.

Murray and McBean hoped the NAACP would use their case to challenge segregation on public transportation. However, the NAACP decided not to pursue her case because the judge threw out the most constitutionally relevant charge and weakened Murray’s legal case. Learn more.

1941: ADAM CLAYTON POWELL

On March 31, 1941, Reverend Powell of Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem led a boycott against two private Manhattan bus lines, the Fifth Avenue Coach Co. and the New York City Omnibus Co. The bus lines refused to hire any Black people except for the job of a porter. In 1939, Powell had started the Greater New York Coordinating Committee for Employment, an organization that led mass demonstrations for the employment of Black workers during the Great Depression. Powell’s organization, along with other Harlem groups, called for a boycott of the bus lines. After a one-month boycott, the bus lines agreed to hire 100 Black bus drivers and 70 maintenance workers. The agreement also required the bus lines to abide by an affirmative action policy that ensured that 17 percent of the bus lines’ workforce was Black. Learn more.

1941: KAMALADEVI CHATTOPADHYAY

In the spring of 1941, the Indian diplomat Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay sat down in the whites only section of a segregated train. When the train crossed into Louisiana, the ticket collector ordered her to move. She refused. The ticket collector left, but soon returned. He asked her where she was from, realizing that she wasn’t an African American. She told him New York. “I mean which land do you hail from,” the collector retorted. Chattopadyay could have told the tax collector that she was a distinguished guest of the United States. In fact, just a few months before her trip, she had tea with Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. Instead, she told the ticket collector, “It makes no difference. I am a colored woman obviously and it is unnecessary for you to disturb me for I have no intention of moving from here.” The collector muttered, “You are an Asian,” but did not make her move. Learn more.

1943: DOVEY JOHNSON ROUNDTREE

In the winter of 1943, while in Miami, Florida on assignment for the first African American Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, Dovey Johnson boarded a bus filled with other military personnel and chose to sit in the front of the bus among white marines. The bus driver demanded that she give up her seat for a white man and threatened arrest. The driver forced her off of the bus and left her behind at the station for many hours. Following this incident, Ms. Roundtree would go on to fight bus desegregation cases as an attorney in the 1955 case Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company. Learn more.

Recommended reading: Mighty Justice (Young Readers' Edition): The Untold Story of Civil Rights Trailblazer Dovey Johnson Roundtree

1944: JACKIE ROBINSON

On July 6, 1944, Lieutenant Jackie Robinson, while stationed at Camp Hood in Texas, was instructed to move to a seat farther back in the bus. Robinson refused and was court-martialed. Robinson wrote to the Department of War and the Black press gave national visibility to the story. The army was worried about bad publicity as a result of Robinson’s sports fame. The court acquitted Robinson of all charges. Learn more.

1944: IRENE MORGAN

On July 16, 1944, Irene Morgan defied Virginia authorities by refusing to change her seat on a segregated bus in Virginia. Morgan was travelling from Virginia to Maryland, when she was told by authorities that she had to move to the back of the bus. Already sitting in the area designated for Black passengers, she defied the driver’s order to surrender her seat to a white couple. When handed an arrest warrant, she tore it up and tossed it out the window. Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP took on her case.

On June 3, 1946, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Morgan’s favor, striking down Virginia’s law in Morgan v. Virginia. Learn more.

1950: WOMEN’S POLITICAL COUNCIL

The Women’s Political Council (WPC) was a civic organization for African-American women in the city of Montgomery, Alabama. In 1950, Jo Ann Robinson, a professor at Alabama State College, became president of the WPC. In response to the arrest and humiliation of Black women who had been arrested on buses, Robinson made the abuse on buses a focus of the WPC.

In 1955, the WPC played a pivotal role in the launch of the Montgomery Bus Boycott when Robinson and members of the WPC printed 35,000 leaflets on the night of the arrest of Rosa Parks and helped distribute them to Black residents over the next few days. The flyers called for a one-day boycott that was a big success and led to the decision to continue. Learn more.

1952: SARAH LOUISE KEYS

On Aug. 1, 1952, Women’s Army Corps Pfc. Sarah Louise Keys traveled from Fort Dix, New Jersey, to her family’s home in Washington, North Carolina. During a stop to change drivers, she was told to relinquish her seat to a white Marine and move to the back of the bus. Keys refused to move, whereupon the driver emptied the bus, directed the other passengers to another vehicle, and barred Keys from boarding it. When Keys asked why she shouldn’t ride the bus, she was arrested and spent 13 hours in a cell. Keys was eventually ordered to pay a $25 fine for disorderly conduct and was released and put on a bus to her hometown.

Her case was brought before the Interstate Commerce Commission and wasn’t settled until 1955. In Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company, the ICC favored Keys, ruling the Interstate Commerce Act forbids segregation. Learn more.

1953: BATON ROUGE BUS BOYCOTT

In late March 1953, the Baton Rouge City Council passed Ordinance 222, which allowed passengers to fill up the bus on a “first come, first served” basis. This allowed Black passengers to sit in the white section of buses if it was empty. The bus drivers received the directive, but refused to comply. As a result of the drivers’ noncompliance, the Ordinance was ruled illegal because it conflicted with the segregation laws of Louisiana. In opposition, the Black community in Baton Rouge began a bus boycott, led by Reverend T. J. Jemison. The locals developed a “free-ride” network that sustained the boycott. It was a method later adopted by the Black community in Montgomery.

To end the Boycott, the drivers and city council agreed to a compromise. It stipulated that the two side front seats of buses were to be reserved for whites and the long rear seat was for African Americans. The remaining seats were to be occupied on a first-come-first-served basis. The Black community agreed to the compromise and the boycott ended on June 25, 1953. Learn more.

1955: CLAUDETTE COLVIN

In early 1955, 15-year-old high school student and NAACP Youth Council member Claudette Colvin was arrested for refusing to give up her seat. As historian Jeanne Theoharis explains:

The driver called out, and the three students sitting in Colvin’s row got up but Colvin refused. “We’d been studying the Constitution . . . I knew I had rights.” . . .

Colvin’s case went to trial in May. Colvin had been charged with three crimes. The judge strategically dropped the charge for breaking the segregation law, but found her guilty for assaulting the officers who arrested her. Therefore, appealing her case could not directly challenge the segregation law.

Colvin continued to attend Youth Council meetings. Rosa Parks made Colvin secretary of the council, trying to nurture the young woman’s spirit and budding leadership. Colvin signed on to be a key plaintiff in Browder v. Gayle, the landmark case that struck down the segregation laws of Montgomery.

1955: AURELIA BROWDER

On April 19, 1955, Aurelia Browder refused to give up her seat to a white person. Her refusal led to her arrest and imprisonment. It also led to the filing of a lawsuit, Browder v. Gayle. Four other Black women were also part of the case — Susie McDonald, Jeanette Reese, Claudette Colvin, and Mary Louise Smith. All had faced racial discrimination on public transportation. Aurelia was chosen as the lead plaintiff on the case. Jeanette withdrew from the lawsuit shortly after it was filed due to pressure from the white community. Learn more.

1955: MARY LOUISE SMITH

On Oct. 21, 1955, at the age of 18, Mary Louise Smith was returning home by way of the Montgomery city bus. At a stop after Smith had boarded and seated, a white passenger boarded. There was no place for the white passenger to sit. Smith was ordered to relinquish her seat. She refused. Smith was arrested and charged with failure to obey segregation orders and given a $9 fine, which her father paid.

Smith’s civil rights activities did not end with her action on the bus. She, along with her sister and their children, were part of a class action law suit for the desegregation of the Montgomery YMCA. Smith also participated in the March on Washington in 1963 and the march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965.

1955: MONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT

Rosa Parks rode home on a cold December evening in 1955. When the bus driver saw that Parks was seated in a part of the bus that an area passenger referred to as “no man’s land” because it was not designated white or Black, he told her to “make it light on yourself” and let the driver have the seats. Parks had recognized the driver. It was James F. Blake, the same operator who had mistreated her in 1943, and she decided to ignore him and looked out the window.

Parks’ decision to stay put was rooted in her history as a radical activist working with the NAACP and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. She was a long time activist and in fact, days before, she had attended a mass meeting about the acquittal of the murderers of Emmett Till.

Historian Danielle McGuire writes: “[Parks’] decision to keep her seat on Dec. 1, 1955, was less a mystery than a moment.” Far from being tired, Rosa Parks saw an opportunity to resist and she seized it. Rosa Parks’ decision pushed local leaders in Montgomery to embark on a 13-month boycott of the Montgomery public buses that ended with the Supreme Court ruling that segregation on buses is unconstitutional. Throughout the boycott, Parks was a key organizer and helped set up taxi services and walking groups that enabled locals to continue to go to work.

On Dec. 5, 1955 the 381-day Montgomery Bus Boycott began. It is one of the most powerful stories of organizing and social change in U.S. history. Yet many people still associate it with an isolated act by Rosa Parks, without the context of Parks’ own life of activism, the decades of protests of Jim Crow on public transportation across the country, nor the role of the Women’s Political Council of Montgomery. Learn more.

1956: TALLAHASSEE BOYCOTT

On May 26, 1956, Wilhelmina Jakes and Carrie Patterson, two students from Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU), sat down in the whites-only section of a segregated bus in Tallahassee. When they refused to move, the bus driver pulled into a local service station and called the police. The Tallahassee police arrested both students, charging them with “placing themselves in a position to incite a riot.” In response, students at FAMU organized a campus-wide boycott of the city buses that attracted the support of local community members.

One local community leader, Reverend C. K. Steele, helped establish the Inter-Civic Council (ICC) to coordinate the boycott. Like the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the organization created a carpool system to provide alternative transportation for local residents and students. Even with much harassment from local police, students and the local community sustained the boycott through December 1956, when the U.S. Supreme Court issued its ruling in a case that originated from the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Shortly thereafter, Steele and other local leaders boarded the segregated buses and sat in seats reserved for whites without being ordered to leave. A month later, the city repealed the segregated seating ordinance. Learn more.

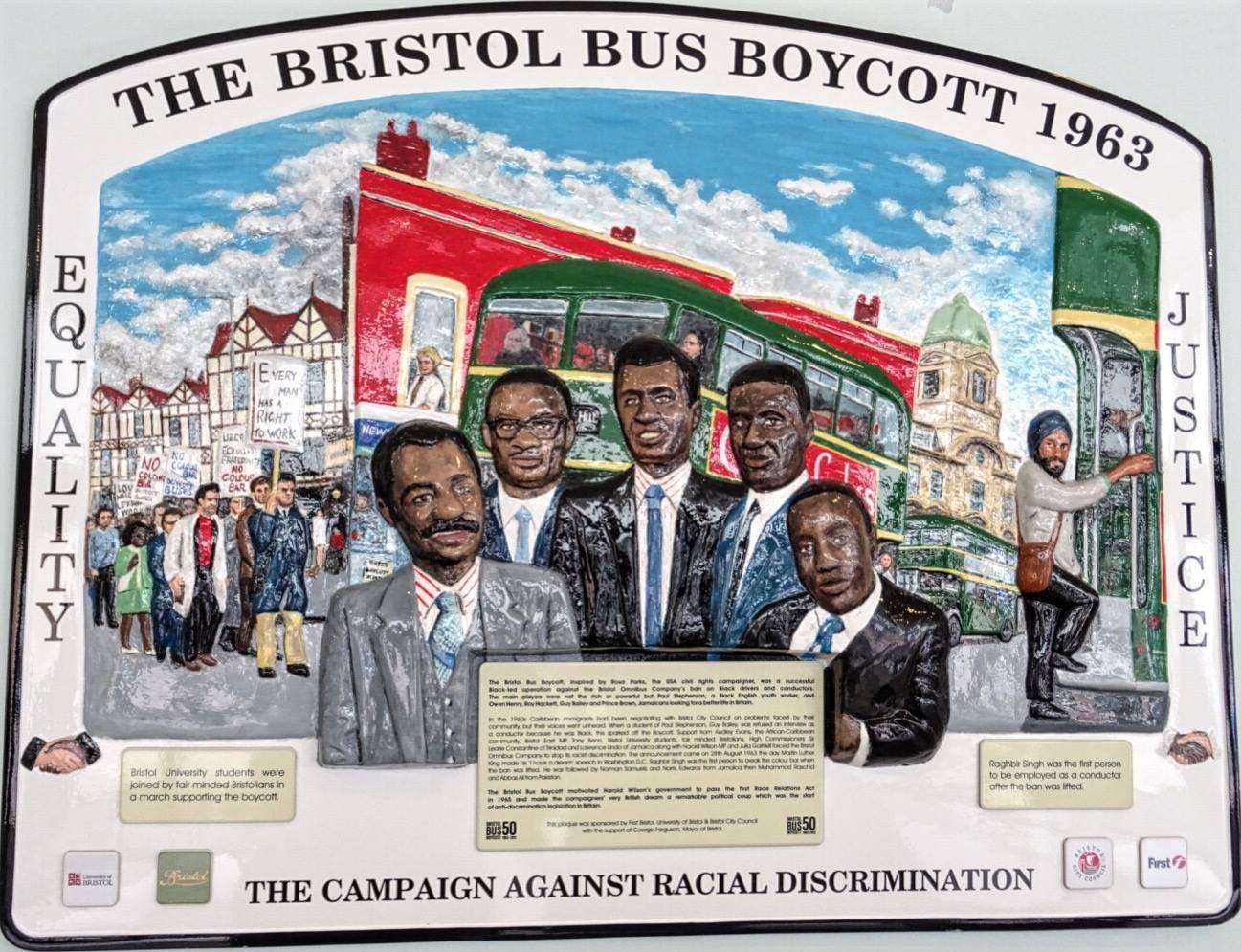

1963: BRISTOL BUS BOYCOTT

Inspired by the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a group of West Indians in Bristol, England, organized a boycott of the Bristol Omnibus Company for its refusal to employ nonwhite workers on its buses. The Bristol Omnibus Company was a national company owned by British Government since 1950. Four young West Indian men — Roy Hackett, Owen Henry, Audley Evans, and Prince Brown — formed an action group called the West Indian Development Council and, along with youth worker Paul Stephenson, planned a bus boycott. The boycott started on April 29, 1963 and lasted for four months until the company reversed its discriminatory hiring practice. On Sept. 17, Raghbir Singh, a Sikh, was the first person of color to be employed by the company, and a few days later two Jamaican and two Pakistani men joined the company. The Boycott was also a key factor in the passing of the Race Relations Act of 1965. Learn more.

1966: SNCC WASHINGTON D.C. BUS BOYCOTT

In 1965, D.C. Transit decided to increase bus fares from 20 cents to 25 cents. Marion Barry, who came to D.C. to set up a local chapter of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), challenged the fare increase. He argued that the fare increase disproportionately affected people of color in the D.C. area. Barry and Edgar H. Bernstein, a former member of the D.C. Public Service Commission, also argued that the fare increase only served to benefit D.C. Transit’s return on investment and was an unnecessary increase in terms of cost. D.C. Transit, however, was not swayed by the criticism. In response, the local chapter of SNCC, along with other civil rights organizations including the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Coalition of Conscience, planned a one-day boycott of the D.C. bus system. On Jan. 24, 1966, an estimated 130,000 riders participated in the boycott, causing a loss of about $30,000. The boycott led officials to back down from the fare increase. Barry believed the boycott showed that “the people have power.” Learn more.

1992: BUS RIDERS UNION

The Bus Riders Union (BRU), initiated in 1992 by the Strategy Center’s Transportation Policy Group, organized a “Billions for Buses” campaign to demand that the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) invest in the city buses instead of the little-used suburban rail lines.

In 1994, the BRU led popular protests against a massive fare hike and obtained a temporary restraining order to stop the MTA. The BRU then sued the MTA with violating Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, in which the government is prohibited from allocating funds in a racially discriminatory manner. The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund went to federal district court and the court issued a temporary restraining order against the fare increases. Learn more.

A reminder that countless more examples can be found in the book Traveling Black: A Story of Race and Resistance by Mia Bay.